By Thomas Clarke Harris

American Rifleman, vol 39, No. 23, March 15, 1906 - page 472

When a bullet leaves the muzzle of a high power rifle, at a velocity of about 2000 feet per second, it encounters two forces of nature which will bring it to the ground, unless stopped by striking some object other than the air. These forces are the attraction of gravity and the resistance of the air. The former acts the same at all velocities, but the resistance of the air is greatly increased at higher velocities.

The amount of resistance or friction of the air, at different velocities, is probably known by those who have given the subject of ballistics much study. Of that ratio I will not attempt to speak, but will assume that the resistance increases as the square of the velocity.

It seems reasonable to suppose that the shape or contour of the projectile has much to do with the amount of friction it meets. A very smooth and symmetrical bullet, having the least roughness of surface, will not only meet with less friction, but its flight will be more steady.

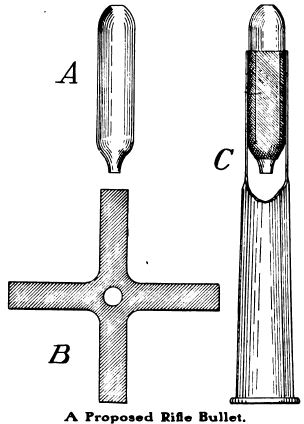

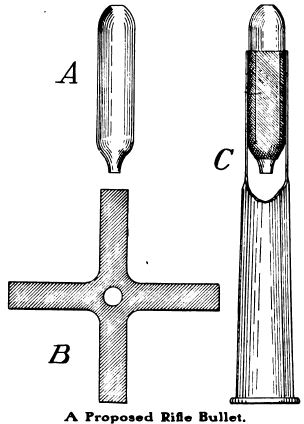

In the rifle bullet of the ordinary shape, there are several annular grooves encircling it, and its base is cut off square with the body. The grooves are intended to carry the lubricant and to take the imprint of the rifling in the barrel, whereby it is given a rotary motion on its own axis. The rotary motion is indispensable, for it serves to correct, in a large degree, any tendency to wobble or to drift to one side or the other.

Unfortunately the grooves in the bullet and the indentations made by the rifling in the barrel makes the surface of the bullet more or less rough, and the great velocity of its flight through the air must sensibly diminish, by increased friction, its striking force.

It is also probable that a roughness or inequality on one side, too slight to attract attention, may serve, by increased friction at that side, to deflect its flight out of a true line.

The rotation of the bullet on its own axis serves to correct such deflections, but is not always entirely effective. We find that bullets will some times tumble, or keyhole, and swerve in an unaccountable manner, possibly due to the causes mentioned. The contact of the naked lead and the steel barrel rubs off more or less of the softer metal, fouling the rifling, and the hard jacketed bullets soon spoil the barrel for accurate work.

If we examine an instantaneous photograph of a rifle bullet, in its flight through the air, we see that it pushes a visible wave of air before it, and the wave streams along its sides and closes in behind it, to fill the vacuum created there. This motion of the air is precisely like the movement of water, when an object is drawn through it end wise.

The square base of the bullet, like the square stern of a scow, must serve to retard its speed in some degree, and for that reason all the fast yachts have a fine run in their afterbody, so that the water displaced may close in at the stern with the least friction.

The four wings of the patch just close around the bullet, with none in excess. The diameter of the bullet, with the thickness of the patch, should be just such as to give the proper fit inside the bore, to take a good hold of the rifling, but not to mar the bullet. Either soft lead or lead hardened with antimony may be used. If desired a soft nose with a hard body can be made.

It seems to me that such ammunition would be an improvement, especially for long range, while the barrel would suffer no harm whatever. The patch, of course, will fall to the ground, a few feet from the muzzle, as with the old muzzleloader, while the bullet should move faster and strike harder, for the reasons stated.

Arranged as described the cartridge case covers all of the patch and would not look different from the ordinary ammunition. With a proper mold and die to cut the patching the rifleman could load his own shells.

Thomas Clarke Harris - Baltimore, Md.