Reloading

WILLIS O. C. ELLIS

Hunter-Trader-Trapper, vol 30, No. 6, September 1915, pages 70-72

The professional sport who wears his hat cocked to one side, carries a gold headed cane, holds to one end of a couple of yards of ribbon the other end of which is attached to a well groomed poodle, and assumes an air indicative of the ownership of one of New York City's downtown business blocks, never wears a ready made suit of clothes. He says the coat does not hang right from the shoulders, draws across the chest, the trousers are not right at the waist, and the whole thing a bum fit compared to the nice, easy fitting garments produced by a skilled tailor. Just so the professional rifleman insists that the best fitting loads for his pet rifle—the loads that enable it to do its best work—are those carefully prepared by hand.

Time was when hand loaded ammunition was inferior to the factory product because the reloading tools were not correctly made, but with the present excellent tools, ammunition that is at least equal and often superior to the best factory loads can be produced. That hand loaded ammunition must be good is attested to by the fact that in some matches, factory loaded cartridges only are allowed to he used, thus barring anyone from using cartridges loaded by hand.

We are perfectly free to admit that the ammunition turned out by the great cartridge concerns does very fine work, but as a matter of economy, when using center-fire cartridges pretty freely we turn manufacturer, do our own loading, and put a good wad of profit in our pocket, for charity you know begins at home. Yes, we like factory cartridges and every time we open the door of the ammunition compartment of our gun cabinet we see a number of different makes and calibers grinning at us.

Tools of the Craft.

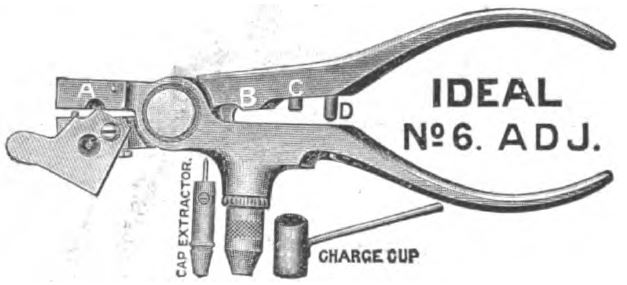

Reloading tools are either of the combination or separate variety. The combination tool has the mould and loading chamber in one and the same implement. Example, Ideal tool No. 6.

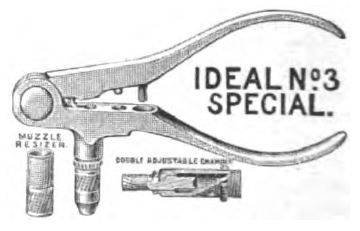

In the separate tool the mould is separate from the part carrying the loading chamber. Example, Ideal tool No. 3.

Both of these types of tools give excellent results, the combination tool being more convenient to take on a camping trip when it is desired to mould bullets in camp as it is self contained; while the mould and separate tool are usually used when much reloading is done.

Ideal Tool No. 3 Special is the best tool yet produced for reloading rifle cartridges, also for reloading the revolver cartridges for which it can be furnished. Used in connection with its several attachments, the shell may be resized, mouth reduced or expanded, re and de-capped and finally loaded in the most approved manner. Ideal Tool No. 10 Special is like No. 3 excepting it is made for use with rimless shells.

Each set of tools is usually accompanied with a charge cup for measuring the powder, but only fairly accurate results can be obtained by this method. For securing the best results the Ideal Powder measure should be used. This may be adjusted to throw any desired amount of powder with great precision and is found on the loading table of every gun crank. Never measure smokeless powder for High Power cartridges in the charge cup. It should always be weighed or its equivalent. When correctly used the Ideal Powder Measure is practically as accurate as scales.

Moulding Bullets.

If there is any one thing we like to do better than anything else in the reloading game it is to mould bullets. Many times have we, during leisure hours, moulded bullets over and over again for the pleasure and practice it afforded. For, after all, moulding the bullet is a pretty particular job as the bullet must fit properly to give best results and this can not be accomplished unless the bullet is correctly cast. Factory bullets are swaged into shape and are consequently quite uniform.

A common fault with bullets cast by beginners is they are shriveled, the cannelures —grooves for the lubricant—do not show up clearly and have flaws resembling worm holes.

These, as well as other imperfections, are traceable to the fact that about nine out of every ten beginners use an old spoon for melting the lead and pouring it into the mould. We are not going to say that bullets can not be made from lead melted in an old mush spoon, for if we had a dollar for every bullet we have run from this kind of a melting and pouring outfit, this fall would find us somewhere in the wilds of New Brunswick hunting moose.

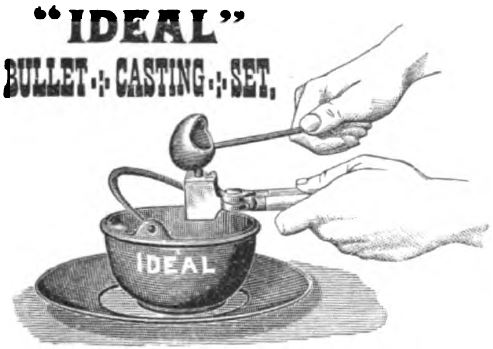

We will say, however, that bullets poured from an old spoon are a sort of "will do" for they are far from perfect. The lead in running from the spoon into the mould becomes more or less chilled and for this and other reasons does not permit the casting of perfect bullets. But by the use of three inexpensive articles the very best bullets possible to produce are easily cast with a little practice.

These are the Ideal Dipper, Melting Pot and Cover, the last named article enabling the melting pot to be placed on any ordinary stove hole. The kettle will hold several pounds of lead, which, when melted is easily kept at an even temperature and holds heat better than a smaller amount. When moulding bullets keep the lead hot enough to run freely but don't get it red hot. A little tin (block tin) added to the lead will make it flow better and also make the bullets slightly harder. To use the tin, melt the lead, add tin, throw in a lump of tallow or beeswax to flux the metal and stir well. If too much smoke issues from the molten mass burn it off with a match and with the dipper keep it skimmed clean.

Keep the dipper in the metal so it will acquire the same temperature and also keep the moulds hot.

A cold mould will chill the lead and produce imperfect bullets. When using the dipper, dip it full and place the nozzle to the pouring hole of the mould and adroitly bring the two to a vertical position. When this is properly done the lead in the dipper and moulds becomes a continuous mass, the greater weight of the lead in dipper forcing the lead in the mould into every nook and corner, producing a perfect bullet. The moulds should be so hot that even after the dipper is removed the lead will, for an instant, remain in the liquid state. To get the bullet out, strike the cut-off with a piece of wood and let the bullet fall on a clean cloth. If the mould fits too tightly it is recommended by some to place a strip of paper between its two halves. This is also recommended when slightly oversize bullets are wanted for a barrel worn a trifle large.

Pure lead bullets can be successfully used in rifle having a slow twist, say from 14 inches up, such as the .25-20, .32 Special, .38-55, etc. But when casting bullets for barrels having a quick twist like the .25-30, .30-30, .22 H. P., etc., they must be made from an alloy that makes a very hard bullet so the bullet will follow the rifling and not "strip," i.e., blown out of the bore across the lands without following the rifling. Such alloy may be made in the melting pot by buying the ingredients, consisting usually of lead, tin and antimony, and mixing them. It is, however, quite convenient to buy "Ideal Bullet Metal" selling at 15 cents per pound—less in large quantity—as making up the antimony alloy is at best considerable trouble. The alloy bullets when driven by fairly heavy charges of smokeless powder should have the Ideal gas check cup affixed to the base to protect them from the hot gases. However, if you can not spare the time to make your bullets, or do not care to do so, you can buy them handcast from the Ideal people (Marlin Firearms Co.) at an extremely reasonable figure and rest assured every bullet they send out is right. Personally we prefer to mould our own for reasons stated above.

Bullet Lubricant.

A good lubricant goes a long ways toward lengthening the life of the barrel and aiding accuracy and should be given careful attention. There are a number of lubricants easily compounded but those that stick well to the bullet give best results. A lubricant having no tendency to adhere to the bullet will do but little good. One of the most satisfactory lubricants we have ever used is made of two parts steam engine cylinder oil and three parts beeswax. In hot weather the amount of bees wax may be increased, making the compound thicker and less susceptible to heat. To prepare: Melt oil and wax in separate vessels, then mix in the proper proportion and stir well. To lubricate the bullet : Dip the bullet in the lubricant base first until all the grooves are submerged, then remove and stand on a clean board to cool. To remove the surplus grease: Cut off the head of a shell for which the bullet is designed and press the muzzle of the shell down over each bullet allowing the bullets to pass up through the shell. The bullets are now ready for loading into the shells or may be put in boxes and stored away for future use.

Cleaning the Shells.

As soon as possible after shooting, the primers should be removed and the shells thoroughly cleaned. This is especially true when using black powder, for if the residue is allowed to remain, corrosion takes place, the powder capacity will be reduced and when the proper charge of powder is used the bullet cannot be correctly seated. A common method is to boil the shells in soap suds or soft water to which has been added common baking soda. Then rinse in clean, hot water—so hot the shells will dry from their own heat when removed. Be sure to dry out the primer pocket and it may be necessary to place the shells in the oven, but don't get them too hot as too much heat will soften the metal.

Loading.

When seating the new primer be sure that it does not, when seated, project beyond the head of the shell but rather have it slightly below the face of the head so it can not be accidentally struck and prematurely exploded. Now that the bullets are moulded and lubricated, the shells cleaned and primed, we are ready to load. After carefully measuring or weighing the required amount of powder, pour it into the shell and seat the bullet by hand as far as it will go. Then place the cartridge in the loading chamber of the tool and close the handles. If the work previous has been correctly done you will have a cartridge equal in appearance to any factory made and in accuracy will not suffer by comparison.

Cartridges for repeating rifles should have the shells crimped onto the bullets so they will not work out of the shells and cause trouble. For single shot rifles for target shooting, reloading is that it permits the production of reduced loads—loads suited to all ranges. Thus users of the .30-30, .32 Special, .30-40, or even the .30 U.S. Army, can produce loads suited to all game from squirrels to grizzlies. This is of great advantage as the use of the big game rifle on small game keeps one in touch with his big game gun and enables better shooting to be done than if the arm were used only during the hunting season.

In the foregoing we have only outlined some of the fundamentals in reloading as lack of space will not permit the subject being fully treated. Those desiring full and comprehensive information regarding the many phases of reloading should send six cents in stamps to the Marlin Firearms Co., New Haven, Ct., for a copy of the Ideal Hand Book. While this volume loudly proclaims that Ideal tools are the best and illustrates and describes the entire Ideal family, it is so full of practical information that it should not be classed as an advertising catalogue and no one interested in shooting should be without it.

(Continued.)

Ed. It might be in H-T-T, vol. 31, which is...

not available...