Forest and Stream, Volume 92, Feb 1922, pages 72-73, 94-95

Reduced Loads For Short Ranges

How To Reload High Velocity Cartridges With Small Charges Of Powder And Alloy Bullets For Lesser Game

by A.L. Bragg

PRACTICALLY every owner of a high-power rifle,

and those contemplating the purchase of one, have given more or

less thought to the problem of reloading high velocity cartridges

with small charges of powder and alloy bullets for short range

shooting. Every shooter recognizes the fact that modern metallic

ammunition is expensive and that the empty shell, which is an

article of mechanical perfection, is the most costly part of the

modern cartridge. It requires the very best materials and skilled

workmanship to manufacture a shell for a high-power rifle and it

seems wasteful to throw away every empty shell instead of using

them over and over again. The continued use of high velocity

ammunition, besides being expensive, shortens the life of the

rifle barrel and sooner or later the sportsman begins to consider

the problem of using a cheap and satisfactory short range load.

Reduced loads of certain brands of smokeless

powder and alloy bullets can be satisfactorily used in high-power

rifles. Black powder or semi-smokeless powders should not be used

in reduced loads because they are not intended for the modern

high-power rifle. Smokeless powders for high velocity loads will

not work satisfactorily when used in small quantities in large

cartridges, because they were designed to burn at the pressures

developed by the full charge loads. However, there is a class of

smokeless powders, like "Marksman" and "Unique," that are

manufactured especially for use in making up a short range load in

high-power rifles. Such powders burn very efficiently in rifle

shells having a large chamber space, developing a strong

propelling blast, without excess heat, and leaving no unburned

residue. Their proper use is not attended with any risk to either

the rifle or the shooter himself, and, if the reloading is

properly done, they will give good satisfaction in every way.

THE reloading of high-power rifle cartridges

with metal cased bullets and full charges of smokeless powder

should be done very carefully, for unless one thoroughly

understands the nature of the load he is using and is prepared to

do the work with the utmost accuracy, he may produce a load that

would bring disastrous results in the best steel rifle barrel

manufactured. The reloading of high velocity cartridges can best

be done by the cartridge companies where the work is done with

great accuracy and the cartridges are subjected to tests that

render them perfectly safe in properly constructed arms for which

they are intended.

Reduced loads for high-power rifles, as

described in this article, are not to be confused with the

so-called gallery loads, or loads limited to short range indoor

target work. A 30 caliber cartridge loaded with ten grains of

“Marksman” smokeless powder (which equals in volume almost 25

grains of bulk black powder) and an alloy bullet weighing from 125

to 150 grains, makes a cartridge suitable for shooting small or

medium sized game at ranges up to two or three hundred yards. The

velocity and accuracy of such a cartridge is surprising, besides

being such a pleasant and clean cartridge to shoot. Such a load

will group the bullets in an eight inch circle at two hundred

yards with the greatest regularity.

The first prerequisite towards reloading high

velocity cartridges with short range loads is to have clean, well

cared for shells. As soon as possible after firing, the primers

should be removed and the shells carefully washed with warm water

and soap, then rinsed in hot water. The shells can be placed in a

warm oven to dry, but they should not be allowed to become very

hot as it will anneal them. Shells that become soft are liable to

fit the rifle barrel too snugly, causing them to stick in the

chamber after firing. It is very annoying to be troubled with

empty shells sticking in the rifle chamber and failing to eject

properly, compelling the shooter to fall back on a cleaning rod or

other device to extract them. Shells should be elastic and springy

so that they will contract to some extent after firing and eject

easily. Heat softens brass. It cannot be hardened by sudden

cooling after being heated, as can be done with steel. Care should

be taken to see that the shells are clean and dry before putting

them away or reloading them, for the least bit of moisture or

dampness will cause corrosion of the inside of the brass case and

may cause deterioration of the powder charge in the loaded

cartridge. A corroded shell is almost worthless and a never ending

source of trouble. Rifle shells can be reloaded on an average of

about five to twenty-five times apiece, depending largely upon the

care they receive and the strength of charge that is used. The

writer has a number of shells that have been reloaded a much

greater number of times and they still show a good state of

preservation.

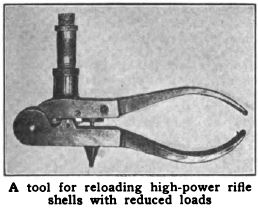

THE first step towards reloading a cartridge is

to seat a new primer in the pocket in the head of the shell. This

should be done with a recapping tool made especially for the

purpose so that the primer will be seated firmly in its place,

thus avoiding misfires or possibly accidents in the mechanism of

the gun. It is a very dangerous practice to seat a primer in a

shell containing powder, and one's safety demands that this work

be done while the shell is empty. After seating the primer, the

shell is ready for the powder.

There are three ways of measuring out the

correct amount of powder for the desired load; mechanical powder

measures, scales, and charge cups. The mechanical powder measure

is the most satisfactory way of measuring out the charge desired.

They can be easily and quickly set to throw any given charge with

accuracy and regularity. Accurate and finely adjusted scales of

the beam balance type and grain weights, make a very dependable

apparatus to weigh out smokeless powder charges, but they require

some patience and their slowness, when it comes to weighing out a

large number of charges, makes the weighing process the least

desirable of the three. The charge cup is a very handy and cheap

powder measure that will do the work very well where a machine to

do the work cannot be afforded, or one does not care 'to bother

with weighing out each charge separately. A charge cup holding 25

grains of black powder will hold approximately 10 3/4 grains of

"Marksman" and if the measure is filled exactly the same each

time, without jarring, it will serve the purpose very well.

Exactly the same amount of powder should be

used in every short range load if uniform results are to be

expected. Powder charges of 10 to 12 grains weight of "Marksman"

or corresponding loads of "Unique" can be used with alloy bullets

in 30 caliber rifles, 10 grains weight in high-power rifles of the

25 caliber class, and about 8 grains in high-power rifles using

bullets of a smaller diameter. Slightly heavier charges of powder

than those given can be used in each class, but as the amounts

named give all the powder needed for their particular use, there

is no need in getting closer to the point where there is liable to

be fusion of the base of the bullet.

Too much powder in a reduced load in a

high-power cartridge will cause the base of the bullet to melt,

resulting in a leaded barrel and a wild-shooting bullet. Bulk for

bulk, practically none of the many brands of smokeless powder will

weigh exactly the same, nor will ten grains of one powder equal

the shooting strength of another of the same weight. Every can of

smokeless powder gives the amount that should be used with any

particular load, and this limit should never be overstepped. Stick

to the brand of powder that suits your particular purpose best,

learn all its peculiarities, and then most of your powder troubles

will vanish.

FITTING the bullet into the mouth of the shell is a more painstaking piece of work than many would imagine. A brass shell cannot be heavily crimped into a hard metal bullet, nor can a shell be resized with a bullet in the mouth of it without deforming the bullet. In black powder shells, where the powder charge fills the shell, crimping is a comparatively easy matter as all that is necessary is to crimp the shell in front of the forward band on the bullet and the pressure of the powder against the base of the bullet will keep it in the desired position.

In smokeless powder cartridges the charge of

powder does not fill the shell and some means must be taken to

prevent the bullet from sliding back into the enlarged chamber of

the shell, as will sometimes happen with bullets in the short

range loads. As alloy bullets are, as a rule, slightly larger in

diameter than the metal-cased bullets in order to shut off all

escape of gas, they may fit tight enough in the shells so that the

cartridges can be handled without danger of the bullets receding

in the shells.

Where the bullets do not fit snugly in the

mouth of the shell and when the mechanism of the rifle demands a

tight fitting bullet, as in a tubular magazine gun, there are four

ways of making the bullet stay in the mouth of the shell where it

belongs. These ways are: using grooved shells, making indentations

in the shells, crimping the shell slightly into the forward groove

on the bullet and resizing the shell so that the bullet will fit

tightly. Grooved shells, having a groove around the shell for the

base of the bullet to rest against, are obtained of the cartridge

companies. Sometimes these shells cause trouble in some arms after

being used several times on account of the shell lengthening out

as the groove in the shell straightens. Slight indentations can be

made in the shells to prevent the bullets from receding by using

what is called a "shell indentor" which will make slight

indentations in the shells for the base of the bullet to rest

against when placed in the mouth of the shell.

By using a reloading tool having a crimping

shoulder, the shell can be slightly crimped into the forward

groove on the bullet, which will hold the bullet in place and

prevent it from receding or working loose and getting out of the

shell. Bullets can be held tightly in place in a shell by first

resizing the muzzle of the shell and forcing the bullet, base

first, back into the shell to the required depth. This method of

seating bullets requires considerable care to avoid injury to the

base of the bullet or scraping the sides of the bullet as it is

pushed down into place. It should be remembered that crimping a

shell does not add to the accuracy of the cartridge and the less

crimping that is done on bottle necked shells, the better results

will be obtained.

Bullets for reduced loads in high-power rifles

are made of one part tin to ten parts lead. Pure lead bullets

cannot be used in rifles with quick twists on account of the metal

being too soft to prevent the bullet from stripping as it goes

through the barrel. While tin gives the bullet toughness and

hardness, it has the disadvantage of having a lower melting point

than has lead. Lead melts at 626°F, while tin melts at 451 °F, and

volume for volume, lead is almost twice as heavy as tin. However,

tin is the most satisfactory metal that can be used with lead to

make a bullet for the lighter smokeless powder loads. Antimony is

often added to bullet metal to give it hardness and prevent

stripping, about 3 to 5 per cent, being sufficient. Antimony melts

at a temperature slightly higher than that of lead and is only a

trifle heavier than tin. It makes the bullet hard and somewhat

brittle, and unless absolutely necessary to prevent stripping, it

is probably best not to use this metal. Antimony will not mix well

with lead without the addition of a small amount of tin and it

possesses the peculiarity of expanding on solidification.

Sometimes it is difficult to secure block tin, and solder,

containing half tin and half lead, can be used.

MOULDING bullets requires a little practice.

The metal should be heated in an iron kettle over a gas or

kerosene flame so that the heat can be regulated easily and kept

uniform, a requirement for the moulding of good bullets. A dipper

made for the purpose, having a nozzle which fits the pouring hole

of the cut - off on the mould, should be used if the best results

are expected. Before beginning to use the molten metal, drop in a

small piece of tallow or a few drops of oil and stir to flux the

metal and make it flow easier. Keep the metal at as low a

temperature as will enable it to flow freely and make good smooth

bullets.

If it is heated to a temperature too high the

metal deteriorates rapidly and the bullets will be porous. The

mould must be kept hot, and if a pair of cotton gloves are worn on

the hands the work of moulding bullets will be made more pleasant.

As the bullets come from the mould they should be allowed to fall

gently on a piece of clean cotton cloth where they can remain

until cool. As a rule new bullet moulds do not cast good smooth

bullets until they have been used a short time and the interior

surfaces of the mould have become oxidized. The mould must be kept

clean and well oiled or it will soon become useless.

A bullet of 125 to 150 grains weight makes a

well balanced bullet for reduced loads in high-power rifles of the

30 calibers and about 80 or 90 grains weight is most satisfactory

for high-power rifles of the 25 calibers. If lighter bullets are

used the powder charge must be reduced to prevent stripping and a

longer and heavier bullet is liable to tip in its flight after

leaving the muzzle of the rifle and destroy its accuracy and

efficiency.

A high-power rifle sighted for high velocity

ammunition will not shoot short range loads correctly. Such a

rifle will shoot to the left and a little low when used with the

short range loads, therefore an adjustment of the sights must be

made if accurate shooting is to be done. Should the rifle be

equipped with a peep sight, similar to Lyman's No. 103, which has

a very fine adjustment for both windage and elevation, the problem

of keeping the rifle sighted for both short range and high

velocity loads becomes an easy matter. By marking the stem above

the adjusting sleeve and marking the windage adjustment for point

blank range with high velocity ammunition at a range of about a

hundred yards, and making similar marks for the point blank range

with short range loads at about fifty or seventy-five yards, the

rifle is very quickly adjusted for either of the two loads.

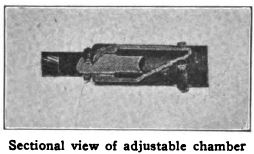

IF trouble is experienced in having shells

stick in the chamber of the rifle, the difficulty can be remedied

by resizing the entire shell in a resizing tool made especially

for the purpose. To resize a shell, the exterior surface should be

wiped with an oily rag and the shell driven into the resizing die

with a wooden mallet. If the resizing tool rests upon a solid

block of wood it will expedite the driving of the shell into the

die. Driving the shell in and out of the die will reduce it to a

size that will enable it to enter the chamber of any arm freely.

Loaded cartridges must not be resized in this manner and no

success can be obtained in resizing shells that are bent, annealed

or corroded.

Alloy bullets should never be fired in a barrel

following the shooting of high velocity ammunition, without first

cleaning out the barrel, as the residue of the heavy load may

cause leading of the barrel. However, it is not necessary to clean

out the barrel after using short range loads before shooting high

velocity cartridges. All alloy bullets should have the grooves

well filled with a good lubricant. A very good lubricant for

bullets can be made from beeswax softened with cylinder oil, or

pure vaseline hardened with paraffin. In either case the materials

that go into the making of the lubricant must be perfectly pure

and free from acids of any nature. A contrivance for packing the

lubricant into the grooves of the bullets should be purchased or

made by the shooter himself. Such an article can be made by

cutting off the base of a cartridge shell having the same diameter

at the mouth as the bullet used, and after filling the grooves

with the lubricant, they should be forced, point foremost, up

through the shell. Be sure there is no lubricant left on the base

of the bullet to come in contact with the powder and deteriorate

the powder charge in the loaded shell.

The writer has had considerable experience in

using short range loads in high-power rifles for shooting small

game and has found them more satisfactory than a 32-20 or 25-20

rifle which are often used for such shooting. My favorite rifle is

a 303 and I have never had any trouble with the short range loads

working through the magazine or sticking in the chamber of the

rifle barrel, and I never go to the trouble of resizing the empty

shells. With a supply of short range loads and a few high velocity

loads, one is well prepared for any game that may be seen during a

day's hunt.

A FEW words about the choice of a bullet would not be out of place in this article. Choose a bullet that is well balanced and combines appearance with other desirable qualities. There are a lot of queer-looking freaks among the various styles of bullets as well as everything else on the market. A sportsman should not stop with the choice of a well balanced and artistically appearing rifle, but he should demand the same qualities in the shells and bullets which he uses. It serves not only to develop a sense of the beautiful, but it gives one more pride in the things which he possesses.