Practical Rifle Shooting.By W. D. King, Jr.

Western Field, vol 4

A WORLD'S CHAMPION.

[We

are pleased to announce that Mr. Dean W. King, Jr., will be a

regular staff contributor to Western Field hereafter, his

initial contribution in this number being the introduction to

a series of articles on practical rifle shooting, which we are

confident will interest and benefit all lovers of the grooved

tube.

No

man in America is better fitted than is he to write about

rifle shooting from a practical standpoint, for Mr. King is

concededly one of the best rifle shots in the world, as well

as a man of great intelligence, practical experience and much

literary ability.

Everything

pertaining

to America's favorite weapon will be intelligently and

exhaustively covered in the forthcoming articles, written in

the clear and understandable style peculiar to himself. The

various peculiarities of manufacture with the attendant

results of each ; ammunition and how to adapt it with best

results; the various hints, wrinkles and little helpful tricks

known to riflemen, to perfect their practice—all these will be

elucidated in full.

As

an evidence of Mr. King's skill as a rifleman we cite his

recent remarkable performance of scoring, in three out of five

consecutive 100-shot groups: 901, 907 and 908 respectively—or

better than 90 per cent, the shooting being done at 200 yards,

strictly off hand, on the Standard American target, his 908

group tying the world's record of H. M. Pope.

In

1,000 shots fired between August 16 and September 27, he

averaged 87.28 per cent. He is regarded as the steadiest

shooter of the rifle in the world to-day, and will try to tell

Western Field readers how to acquire a similar

proficiency.—Editor.]

PART I -- The Beginning (pgs 61-63)

TO BEGIN at the beginning, I wish to disagree with those authorities on rifle shooting who make the claim that rifle shots are not born, but made—I claim the reverse. Of course it is possible, and is frequently the case, for one who has not any natural inclination for the sport to become a good rifle shot. Any man who has a reasonably good nerve and eye, combined with good judgment, may by a careful and conscientious practice become what would be called a first-class shot.

A great deal depends upon the way one gets started at first practice, especially if he has not a natural instinct for the game. Many people have started in by shooting a large gun with a heavy recoil and have, consequently, been made so " gun shy " that they never got over it, whereas if they had started in with a small caliber, and learned how to hold and pull without flinching, they would have developed into good marksmen. A natural born shot will not pay so much attention to the size and recoil of the gun at the start, as every new gun or load he tries simply gives him an appetite for more.

Of course, there are a great many "natural born shots " who do not develop into even good shots, but that is always traceable to some definite cause, such as some physical debility of the eyes, muscles or nerves, and oftentimes to the excessive use of tobacco or liquor. Now, I will hear you say that the best shot you ever saw used both tobacco and liquor all his life. I will admit that this is generally the rule—most good shots of my acquaintance do, I know. Perfect physical condition, however, will go a long ways when it comes to a match or a long string of shots where the strain on a man's nerves will tell.

I have known of many cases where a man was practically a champion in his class or club in practice, but who would " fall down " badly whenever it came to a match or a test where nerve counted. There have been many phenomenal scores made by people who were badly under the influence of liquor. But for good, steady shooting, day after day, and in the times when you need every point that can be made, give me the man that does not indulge.

In my own case, which may be a good example and one which I naturally know more about than any other, I certainly consider it was born in me as my father was considered the champion of New Hampshire in his day, and his father and grandfather before him were noted shots. On the "other side of the house" my grandfather was a "dead shot," and during his Western life among the Indians and on the trip to California in '49, did shooting that proved him an expert.

As far back as I can remember I have been "

crazy " for a gun, and my parents tell of my lying flat on my

stomach on the floor with a picture of a gun before me by the

hour, perfectly happy, when I was still in kilts. I owned and used

several " guns "— .22 caliber "Captain Jack" revolvers and the

like—years before I was " old enough," as my parents then told me,

and was considered quite an expert by my playmates, who gave me

the title of " Dr. Carver "—a pseudonym which still clings when

among the old crowd.

Every holiday, and many times after school hours, I was after something and generally got it, as I was very lucky in finding and killing my game; it seemingly came natural for me to find it and killing it was no trouble. I always looked in disgust upon any of the boys who would take a rest—and especially with a shotgun as they sometimes did. I always shot strictly off-hand and believe it the proper way to begin, as there are very few times when a man can get a rest when hunting and if he has not practiced off hand shooting he is pretty liable to score a miss.

My target shooting career began at the regular turkey shoots that were always held at Thanksgiving and Christmas. At first I used to "spot" the shots for those who were shooting and at that time had eyes good enough to see a bullet hole easily at sixty yards. Sometimes I would be permitted to shoot a shot or two, which well repaid me for my trouble.

When I was able to own my own target gun (a .32-20 Marlin repeater) I had great expectations; but I made the mistake that thousands are making every day, of thinking that anything that was .32 caliber would shoot in a .32 caliber gun. Most people, the same as I did then, think that if you have ammunition for the gun and it does not shoot well, that the gun is no good. In nine teen out of twenty cases where a gun is condemned the fault is with the ammunition, and if it is properly loaded, using the right kind of powder and the right sized bullet of proper hardness, any modern gun of standard make will shoot much better than any man can hold it.

Many people think that factory ammunition should certainly give best results In a gun made by the same people, but in a majority of cases there is some particular load that will do better work if one will only experiment a little and find out what it is.

Of two guns of the same caliber and made by the same factory one may shoot considerably better than the other with a certain load. So do not hastily condemn the apparently deficient gun, for generally a slight change in the powder or bullet will make it shoot perfectly. There are very few poor shooting barrels ever get out of the factories, the fault in most cases is with the "man behind the gun" or the job lot ammunition employed.

To return to my own experience, I got my sights just to suit me, loaded up my shells and proceeded to make a target. The last ten shots—sixty yards at a rest, they always shot at rest for turkeys—were in the size of a dollar and several of them were " tacks." This was very good with open sights. I then proceeded to mould some more bullets and load more shells for the turkey shoot next day. I do not remember what I loaded them with; I only know that the lead melted and made the bullets and I had powder in the shells.

The shooting match next day was "looking good to me," and my friend and I took a buggy along to bring home the birds. I could not seem to get my sights adjusted right at the shoot and kept changing them; I also changed the size and color of my " spot," yet for all that I could not keep my shots in a space the size of your hat. Of course, I was “joshed " a good deal, and when I finally took my last drink of cider from the farmer's keg and started home with my one turkey (a scratch) I was much disgusted and had a gun for sale—for, of course, it was that gun!

From that time on I began to learn that anything that was merely lead and .32 caliber, with any kind of powder behind it, was not exactly to be explicitly relied on to do record shooting with. That same mistake is made and made every day, and by people who have not only the best outfits that money will buy, but who have had enough experience in rifle shooting to know better.

A very slight change in some small detail of making your ammunition, loading, cleaning and taking care of the gun will some times produce results that are astonishing. In some succeeding articles I will try to cover some of the above points and elucidate to the best of my ability the principles, knacks and wrinkles that underlie and constitute the theory and practice of modern rifle shooting.

PART II - Physical and Mental Conditioning (pgs

148-149)

PHYSICAL condition, as is mentioned in my first article, is one of the principal, if not the most essential feature, in fine rifle shooting. It makes no difference how fine an outfit a man has and how well he has it trained: if he is not in condition himself he will not do good shooting. I attribute my own success entirely to good condition and abstinence from stimulants of all kinds.

I use neither tobacco nor liquor in any form, abstaining even from tea and coffee, except when on hunting trips. There I take a little coffee to warm me up in the morning or as a bracer after a hard day's trip. Of all the stimulants popularly used I regard tobacco as having the worst effects on one's nerves. One of the best shots in this part of the country, who at one time—and that only a couple of years ago—was one of the " scrubs," had smoked a great deal and his nerves were not able to stand any kind of a strain, especially that incurred in match shooting. If it only required a " 3 " to win the match on his last shot, he would invariably go to pieces and make a " 2," some times even missing the whole target. He was fortunately a man of good will power and liked the sport so well that he gave up smoking, and thereafter improved steadily until to-day he is a "top-notcher" and can make as good a shot at the wind-up as any man of my acquaintance.

Liquor, tea and coffee, when used moderately, do not have as bad an effect on the system as tobacco, because the effects are not retained in the system so long. Nevertheless, a man can not hope to be at his best at all times unless he radically eschews their use.

Of course, individuals differ in temperament, and occasionally some one man's experience may be diametrically opposed to this theory. A peculiar case once came under my observation. It happened that the party in question was out to a dance in the country the night before a shoot and was having a " good time," with all which that implies. About 2 A.M., as they were getting ready for the last quadrille his horse broke loose and started home alone, taking an easy trot and keeping the road as well as if being driven.

His owner on being informed of the fact grabbed his hat and started after him at a good gait, about one- third of a mile behind, and to the surprise of every one returned in about an hour and a half with his truant animal. He had run the horse down after going about five miles, and came back to finish the quadrille.

Driving home in time for breakfast, he filled up on strong coffee, and getting his gun and ammunition together went to the range (without a wink of sleep) and shot twelve ten-shot strings which, to the surprise of everybody, were as good in average and total score as any ever shot on that range up to that time. This was one of the proverbial exceptions which prove the general rule.

I have been asked a good many times how I train for a shoot; what I eat, how much I sleep, what exercise I take and what brand of "nerve tonic” I use. I do not train at all, and make no special preparation whatever for a shoot. I take a cold sponge bath every morning and a good rub down with a Turkish towel, but do this only because I like it and not as a matter of training.

I eat anything I want and at any time up to the minute I begin shooting. In regard to sleep, 1 do not go to bed any earlier before a shoot than usual, in fact I prefer a little less sleep than ordinarily, and have done some of my best competition shooting after traveling all night with but very little sleep. The nerves are not at as high a tension if one is a little tired and our movements are slower and more even, insuring more regularity in holding.

If possible eat a good hearty meal about two or three hours before you begin to shoot; this gives your food time to be partly digested and you feel contented and comfortable.

It is only after I have started shooting that I pay more attention to myself than usual, especially if I am shooting for a record or in a match. When I have once started on an event of this kind, I try to shoot at as nearly regular intervals as possible, and prefer not to wait but a few seconds after being loaded and ready. There are several advantages in this: your gun maintains an even temperature and by shooting fast you more readily detect any change in wind or light—an important factor where every point counts.

I do not stop to eat, but if I get too hungry will take a bite of something between shots—just enough to keep my stomach from feeling faint, and very seldom drink anything while I am shooting. In fact, I prefer to be moderately hungry and thirsty. To stop and cat a hearty meal would upset me for several hours, and I have convinced a good many others that such effect is common to all riflemen. There arc, however, exceptions to this rule as all others, and 1 have known men who made the best scores of their lives just after a hearty dinner.

Another thing I try to do is to set every muscle in my body as near as possible in conformity to my shooting position and keep them there. I do not even sit down from the time I start shooting until I am through, preferring to keep an upright position and my legs straight.

Some people advocate long deep breathing just before getting ready to fire, but I believe the benefit derived from it to the lungs and heart are more than offset by the disturbance of the muscles of the body, which, of course, affect the nerves also, so I breathe naturally at all times. This, of course, makes more difference where the arm rests against the body than in the old position of strictly off-hand shooting.

These points may seem unnecessary to the majority of shooters, as it is not pleasant to be thirsty and hungry, or to stand up when you would like to sit down and rest, and if one is shooting only for recreation they would make no particular difference. But a man shooting for a record or in a match wants every point possible, and will put himself to some little inconvenience to get them.

I have shot as high as 170 shots from a heavy muzzle-loading gun, loading it every shot and walking about forty feet each time to the score in less than six hours without stopping to take a bite or drink, and not sitting down once.

In my record score of 917 I shot 120 shots in about three hours and did nothing but load and shoot, and had gone without anything to eat or drink for nearly seven hours before finishing my shoot.

In order to keep all one's muscles and nerves in proper condition it is necessary to have a gun that fits as near as possible, so that it will not tire or strain one at any point, because if it does you will soon tire out and then bad shots and flinching are sure to follow.

There is not nearly enough attention paid to this point, as most of the guns used to-day do not fit their users correctly. In my next article I will try and explain how a rifle should fit and how to find out when it does not fit.

PART III - Rifle Fit and Stance (pgs

222-223)

ASIDE from the accuracy of a rifle, the most important point to be considered is the fit of the arm for off-hand shooting.

The factory-made stock is all right for a light-weight rifle, where the sights are close to the barrel, but for an accurate rifle of heavy weight they arc very far from what they should be. There are hardly any two men that are built alike, and for the finest work every man should have his gun made to fit him just the same as he would a suit of clothes or anything else he wanted to be just right.

Many of our riflemen are shooting rifles which they erroneously think fit them perfectly; this is simply because they are " used " to the gun and a certain position; when, however, these gentlemen get hold of a rifle that really does fit correctly they are astonished, not only with the way the gun feels to them, but at the results achieved from using it.

The ordinary guns have entirely too straight stocks, and are too low at. the comb; the stock makes you " hump " your shoulder up away above its natural position, with your elbow raised to the same height or higher, which is not a natural position. Then you have to screw your head down to get to your sight, and then it does not more than touch the comb of check piece. I have seen some very finely made rifles with fancy stocks and cheek pieces which were being shot with sights elevated for 200 yards or more, showed their cheek pieces to be of no value whatever, as the cheek did not even touch them.

If there is any one time when a man does not want a single muscle or nerve in his body strained it is when he is rifle shooting; this is especially true in fine target work, where every fraction of an inch counts and where one has to hold so long. One must be in a comfortable position or he will not do steady shooting, and that is what counts in a long string of shots. Besides, if one is on a strain at any point he will soon tire and not be able to hold up to his standard after a few scores, but will get so unstrung that he can not hold good and will also be liable to flinch and pull when not intending to.

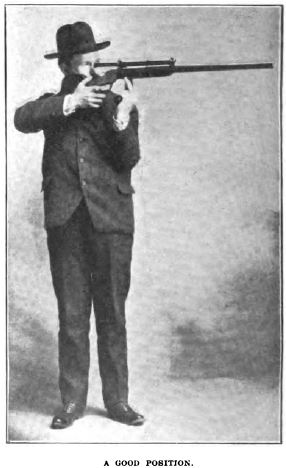

I will first try to explain what I consider the proper position in which to stand and hold the gun, and then how to find out when a gun fits as it should.

A rifleman should stand firmly on both feet, with the weight equally distributed, as in that position he can certainly stand stiller than when putting most of his weight on one foot. Of course there are many people who can get an easier position for their left arm by leaning back than by standing erect, but I think the advantage is more than offset by the swaying of the body.

To find out if the gun fits you, stand erect, or in your usual position if you prefer, and fit the gun to you in the usual way, with your eyes closed. Then relax all the muscles in your back, arms and shoulders, letting your elbow drop toward your body by its own weight and the weight of the gun. Also raise your head to a natural and comfortable position, then open your eyes and see where your sights are, and where they should be. Wherever it seems they should be when your eyes are closed is exactly where they should be when the eyes are open. Have drop enough in your stock so that your arm and shoulders can hang in their natural position, also raise the cheek piece high enough so that you get a good rest for your cheek when your neck and head are in a natural position, so that when you feel perfectly comfortable you can open your eye and look directly through the sights.

The stock should be short enough so that it is no strain to reach the trigger; your hand should also hang in a natural position, and there are several styles of special finger levers made that are a great help. Relaxing the muscles of the shoulders, arms and wrist gives one a much better control of the trigger finger.

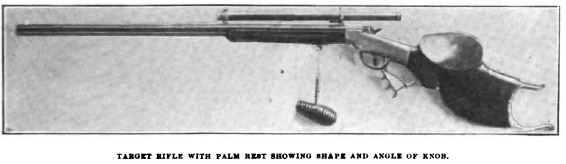

A good palm rest is also an important part of a rifle's appointments, as it is by its aid the gun is mainly " held " and holding is an important part of rifle shooting. I do not think that sufficient attention is paid to this part of the arm. Most people are shooting palm rests that are entirely too long for them, causing a decided angle at the hand and knob. It should be so adjusted, and of such a length, that the pressure would be in a direct line from where the palm rest fastens to the forearm, through the stem, wrist and arm, to the elbow. This gives better control and does away with the leverage where the angle it formed, which leverage is a strain and very tiring. The shape of the knob is also an important point.

Most of them are "door knob" shaped, which forces the hand back, causing an angle at the wrist, and also a strain. The bar running horizontal is also a mistake, as it places nearly all the pressure on the thumb, where the other side of the hand is much lower and does not receive any of the pressure whereas it should be evenly distributed, as the broader the base for your rest the better control you will have especially of the side motion.

Let the left arm rest comfortably against the body by its own weight and the weight of the gun, whether it touches the hip or not; don't try to force it into any unnatural position.

The rifle should also be at the proper elevation without having to change the position of the body backward or forward, and can also be accurately determined by finding a comfortable position with the eyes closed, and the palm rest adjusted accordingly. Plenty of practice on these points, with the eyes closed, will soon determine small points that will prove very beneficial in actual shooting if the gun is otherwise made to conform to the shooter's personal requirements.

PART IV – Iron Sights and Scopes (pgs

304-305)

THE use of various sights for target shooting is largely controlled by the local conditions obtaining where one happens to reside. There are many places where they still adhere strictly to the open sights and look with disgust upon any one who tries to deviate from the old-time custom. This, however, applies only to turkey and beef shooting, in localities where they have no regular shoots upon regulation targets and at regulation distances.

Many and various are the kinds of sights used by our best target shots, and each one has its following; there are many experts in each class, so the matter is largely a matter of individual preference.

However, the two most used at the present time are the regulation peep for a rear sight, with an aperture for front, and the telescopic variety, which is now allowed by a great many of the Eastern clubs and associations, and which is proving very popular and is entirely practical, even for game shooting.

I will give my ideas as to the best sight for target shooting in each class, having made, tried and experimented with a good many of all varieties. For an open sight for target shooting I prefer a-medium-sized black bead in front, with a rear sight that is thin and perfectly level across the top, with a good-sized semi-circle for a notch, the notch beveled away from the eye or leaving a perfectly sharp edge toward the eye; this prevents blurring to a great extent, so eliminating one of the principal troubles with open sights.

In sighting, draw the top of the bead down so that it shows all of the bull's-eye (black) above the bead, forming a figure 8 out of the front bead and bull's eye. You should also see the full bead clear in your rear sight, and not try to draw it down fine in the notch. This makes a sight that, while looking very coarse, is quick to catch, easy to see without straining the eyes, and very accurate. This is the sight I used on the Hear target at the National Bund shoot at San Francisco in 1901, tying for high score on the second score fired. The same gun and sights also won eight of the principal prizes on that target, although it was not brought to the grounds until the last three hours of the shoot on the last day.

The next best sight is the "pin-head" or "bead" sight, which is generally used with a hood over it in combination with a peep rear. Right here I want to say that most of the riflemen are using too small holes in their rear sights—many of them being so small that they look smoky or fuzzy—which is a bad strain on the eye and makes one slow in catching sight, necessitating, of course, one's hold a longer time than needful, and is therefore tiring on the nerves and muscles as well as on the eyes.

Have them large enough so they will look clear to you. Different eyes require different sizes, but have yours so it looks clear to your sight. Your eye naturally finds the center, as the center is much clearer than the edges. You will then be able to shoot and see quicker and better without straining yourself all over.

Hold the pin-head at the lower edge of the bull'seye, making, as before mentioned, a figure 8 out of the combination. By holding under the bull's-eye it enables one to detect the variation much more easily than by holding right on it, as most people after get ting the front sight on the bull's-eye will move it off again to see if the bull's-eye is still there or to see if they are not holding a little too high and mistaking the top of the bead for the bull's-eye. a mistake very often made, especially if the light is bad or one's eyes are not good.

I prefer a pin-head that appears about the same size as the bull's-eye, as then you can not only make a perfect figure 8, but can tell positively if you arc doing it. If not, the size of the bull's-eye should be one which appears smaller rather than larger.

Many of the long-range shots, when they shot with a body rest, used to prefer to hold the bead at the side of the bull's-eye, and at the same height. This enabled them to hold for wind without destroying the elevation, something one has to watch closely if holding off for wind, and sighted to hold under the bull's-eye.

In using an aperture (called in some places a “ring bead"), there are many sizes, from very small with thin rims to very large and thick rims. While I do not prefer an extra heavy rim, I want it to show perfectly black and distinct; if they are too thin they blur.

In size I prefer one that shows what appears to be a clear white ring around the black of about two and one-half or three inches; some use a great deal larger than this, but I prefer this size, as it allows the eye to concentrate on a smaller circle and at the same time shows clearly. It allows for a little variation without losing sight of the black outside the aperture, and allows you a little time to calculate when the bull's-eye will be in the center.

The principal fault with too small an aperture for offhand shooting is that the bull's-eye flashes into the center so suddenly and remains there such a small fraction of time that most people try to pull too quick, and flinch in consequence. They know that it will only remain there an instant and practically “jump" at it before it gets away; this as a rule results in a bad flinch and the habit, like most others, grows and is hard to overcome. At one time I would flinch about seven to nine shots out of ten, and consequently did bad shooting—and made very hard work of it, too!

Have your aperture plenty large enough so that you can see when the bull's-eye is coxing to the center, and you will be able to pull more deliberately and do better shooting. The aperture is not affected as badly by changes in the light as is a bead, although all sights are affected more or less by such chances.

The telescope is of more recent adoption, and is proving very popular. 1 fully believe that it will soon be allowed in all of the big shoots of the country, but people must be educated up to it, the same as they have to the other sights, heavy muzzle-loading barrels, palm rests, et cetera.

The telescope has been modified in length and price until now one may get a first-class glass that is short, easily detached from the gun—and at a very reasonable price, considering the grade of the glass. It is not necessary to have a long or full-length glass for accuracy, as many people suppose, for the short one is just as accurate, as you do not look through or see the object through the lenses, hut simply sec the reflection of the object upon the front or object-lens. The only possible advantage a long glass would have over a short one would be the greater distance between the mountings, making the adjustments for wind and elevation a little more delicate. With the present manner of changing by the use of micrometer screws, however, the long glasses are not considered necessary. For off hand shooting I prefer a glass of about four teen inches length, three-quarter-inch tubing and detachable mountings, which allow the glass to be put on and moved very quickly and easily, making the gun much easier to handle and get into a case. It also prevents the glass from being knocked out of line—a very common occurrence where the glass is left on the gun. By this arrangement one may also use the same glass on several different guns without a great amount of trouble in changing them.

For off-hand target shooting I would advise a low power, especially for a beginner or one who does not hold pretty steady. From two to five-power would be the best. The four and five-powers are very popular among the best shots using telescope sights; they give a large, clear field and appear to hold steadier than the higher powers. Some of the best shots, however, are using as high as twenty-power for off-hand shooting, but that is a better power for rest shooting, where they can hold them perfectly steady and draw it down to one sixteenth inch, which is not necessary for off -hand shooting.

For off-hand shooting I also prefer a medium coarse cross-hair—one that you can sec distinctly without apparently paying any attention to it. This enables you to put most of your attention on the target and pulling the trigger. I also prefer to hold (or try to hold) my cross-hairs where I want the bullet to strike, while a few hold at one edge of the bull's-eye, in the white, so the cross-hairs show plainly, and have the rifle sighted to hit center from that hold.

A telescope docs not help one's holding at all; in fact, in makes some people nervous, as they can see every little move made and they think they are moving more than they really are; but it allows one to see exactly where they are holding and can tell when they are just right.

It also enables the old man, or the man with poor eyesight, to get back into the game, whereas, if these sights were not allowed, they could not shoot with any satisfaction. Why handicap an old man who probably loves shooting as well as his younger and more fortunate brothers, by compelling him to use sights that he can not see to make a good score with? Just as well handicap the young man than can see perfectly, by compelling him to shoot a gun that would not shoot better than, say, a five-inch group, or as good as the older man can see to shoot his. This would be just as reasonable-— but you would hear a cry that would deafen you if such a thing were attempted. Allow every man what he wants and what his condition requires; give a man the privilege of using the best gun he can get, but also allow him the use of the best sights, so that he may get the best results possible —and it's results that we arc all after. We should be broad-minded and progressive, as we are living in the age of progression.

PART V Moulding Bullets (pgs 383-384)

THE moulding of bullets does not seem to be much of a trick to the ordinary man or one unfamiliar with the whims and exactions of a genuine rifle crank.

A great many riflemen—and many of them that are considered experts, too. in their locality—are moulding and shooting bullets that are very far from perfect, but are considered first-class by those who really do not know a good bullet when they see one.

Of course any one can melt lead and pour it into a mould, and among a great many this is considered all that is necessary. They will shoot, however, and even do fairly good work; but a great many times a gun Is condemned as a poor shooting one. or its user deemed a poor shot, when the fault is almost entirely due to the bad or irregular bullets employed. I have seen riflemen who were excellent shots—and had been such all their lives—shooting bullets full of wrinkles and varying 7 or 8 grains in weight and several thousandths of an Inch in diameter and expecting them to shoot all in the same hole; if they did not, the gun was " no good."

It is just as easy to make good bullets as poor ones if one will take the trouble to get every thing right and keep it so. In the first place, you should have a good even heat for your lead, and maintain it all the time you are moulding. Do not have your lead red hot part of the time and nearly cold at others. A gas or gasoline stove, or a plumber's forge is the best to use, as in either of them the heat can be kept absolutely uniform. Have plenty of lead In your melting pot so it will hold heat. Mix up five to ten pounds or more, according to your pot's capacity, and do not mould down to the last of It, but keep two or three pounds in the pot all the time. Get it very hot, but not red hot, as that oxidizes It very fast and allows the bullets to vary too much when they cool.

Have your moulds and dipper very hot. The Ideal dipper is the best tool made for the purpose, and should be left in the lead all the time when not in the act of pouring into the moulds. The moulds should be thoroughly and evenly hot, not hot on one side .and only warm on the other; of course they will soon get heated by the process of continued moulding, and if one has time, it pays to reject the first dozen or two of bullets, throwing them back into the pot to remelt.

If the surface of the lead in the melting pot Is large enough to admit it, it may be covered with powdered charcoal except a small place In the center to dip through; this will keep the surface of the lead hot and prevent it oxidizing and the constant " skimming " of the dross.

An iron ring, large enough to dip through, will float readily on the lead and keep the charcoal from being dipped up in the dipper.

When you have everything ready, dip the dipper full of lead and fit the sprue hole of the mould over the nozzle of the dipper, holding the latter in a horizontal position, then quickly turn the mould and dipper together into a perpendicular position and hold an instant to allow the weight of the lead in the dipper to compress the lead in the mould and force it to the bottom of all the rings. Then turn mould and dipper back to the original position and when you release the dipper have a good big drop of lead on the moulds. The lead should be hot enough so that you have to wait a few seconds for the lead to cool In the moulds. Cut off the sprue neck and drop the bullets carefully on a cloth or some thing soft to avoid marring them.

If the moulds are in good condition and properly ventilated you can not help getting perfect bullets every time. I do not have to throw out more than two or three in a thousand, and these few result only from carelessness in not working right. By doing this and using a little patience and practice one may soon make perfect bullets.

In moulding bullets I always wear a heavy pair of asbestos-treated gloves and cut the bullets oft by pressing the cut-off with my thumb or finger instead of striking the moulds, which is apt to spring them or Jam them and cause them to stick. When you run the last bullet leave it in the mould, not even cutting it oft, and put them away that way. It is a great protection to the moulds from being jammed and keeps the inside in perfect condition.

In shooting to get the best results, the bullets should never be seated In the shell, but seated Into the grooves of the gun with a bullet seater (if a breech-loader) ahead of the shell; this allows the bullet to start its rotary motion as soon as It starts. In place of jumping straight from the shell to the grooves.

Experiments made from machine rests prove that a gun loaded this way will give much better groups than when loaded in the shell, especially if it is crimped in by a loading tool.

If you load your shells full of powder and want an air space between the powder and bullet, seat the bullet further up in the barrel, the more air space there is the less a bullet will upset, and it also lessens the recoil.

If your bullets are soft and you don't want them to upset too much, give plenty of air space; if hard, and upset is wanted, seat them against the powder.

I know of an expert shot who makes his bullets out of "any old thing" and then finds the elevation by simply giving them air space, some times getting them so hard that he has to use F. F. F. G. powder and seating them down on the powder, at others using one-half Inch air space and F. G. powder. If a bullet fits a gun properly and is of the right temper (1 to 30 usually) it should have about one -eighth inch air space.

I have been asked many times just what performance I go through in loading a muzzleloader or false-muzzle gun to be sure I do not shoot without a bullet, or with two bullets, or one only seated into the muzzle. Many a fine gun has been ruined by not having the bullets In their proper place. While I have shot with out a bullet several times, I have never shot two or one from the muzzle, or shot my muzzle away. When I have fired I open the breech and remove the empty shell, go to my loading bench, set the gun in the rack, put on false muzzle, take bullet seater In one hand and fish up a bullet with the other, place bullet in starter and start it in the barrel; then I remove starter and seat bullet with seating rod and leave it in the gun. In the meantime I have kept the empty shell In my left hand all the time; I decap and recap it, load from loader, put an oleo wad over it, and set It beside the gun.

Do all this before doing anything else, then, when you get ready to shoot, and find the rod in your gun, you know there is a bullet in your gun and that it is clear down; pull out your rod with one hand and remove false muzzle with the other, and you are ready and sure.

In using 3 grains smokeless for priming I find it is unnecessary to clean a shell, but always leave it loaded when through shooting, as that prevents it from corroding. I have shot one shell nearly 3,000 times without cleaning it. and it is still in good and serviceable condition. It seems wonderful that a shell would stand that many shots, but it has not broken yet, although It Is worn so thin you can dent it easily with your finger-nail and is splitting a trifle at the muzzle, which is sharp as a knife. I can seat the primer with my thumb, but it does not blow back. It not only shows a wonderful shell but a perfect chamber in the gun.

The shell is a .32-40 Winchester smokeless, and the gun was made and chambered by George C. Schoyen of Denver.

When using a breech-loader I seat the bullet the first thing after laying the gun on the bench, and leave the bullet seater in the chamber until ready to go to the stand; then I know my bullet is in the gun.

PART VI Holding the Rifle (pg 475)

A VERY Important point in rifle shooting, one very little understood and therefore having but very little attention paid to it, is the holding of the rifle in the same position and with the same firmness and pressure against the shoulder every shot.

That is the reason so much better results are obtained by shooting a rifle from a machine rest in determining its accuracy.

Some of our most expert rest shooters, with their perfect rests at both ends of the gun, have done nearly as well as with machine rests, but the secret of their success In this line is due to their being able to hold the gun in practically the same manner for each shot.

The uniformity with which a gun is held against the shoulder, the pressure of the hands, and rigidity of the arms and plan of grasping the gun, all play an important part in all kinds of shooting, whether it be done with a rest or offhand, with a rifle, pistol, revolver or a shotgun. The effects are the same, and your success will depend largely upon your ability to always " hold " the same under all conditions and circumstances.

Of course, the heavier the gun the less the effect from a difference in holding. While a heavy barrel holds steadier than a light one, and the motion Is not so fast as a light one, the reduction of variation from irregular holding is another point in Its favor. There are hardly any two persons who can shoot the same gun with the same degree of accuracy; part of this is, of course, due to the difference in people's eyes and their manner of sighting, but a great deal of it is due to the difference in holding.

Any gun will always shoot higher from a rest than when shot offhand; the difference will vary according to the weight of the gun, weight of bullet, charge of powder, velocity, pressure with which the gun is held, the substance upon which it is rested and upon the distance from the muzzle of the gun to where the rest is placed.

The lighter the gun, the higher the velocity; the tighter the grip, the harder the rest, and the nearer the muzzle the gun is rested, the higher it will shoot.

A sack of sand is about as good a thing to rest a gun on as can be ordinarily found, and the barrel should be rested ahead of the forearm and a little more than half the way up the barrel from the breech for good results, but will vary a little in different guns according to weight, position held, load. etc.

The reason a gun shoots higher from a rest than offhand is that a rest, being harder and more solid than the hand and arm, offers more resistance to the recoil and forces the muzzle of the gun higher after the explosion takes place and before the bullet leaves the muzzle. The natural recoil would be straight backward, but the resistance at the butt, being below the line of the bore, naturally forces the muzzle upward, and the tighter the gun is held, so preventing a backward recoil, Increases the upward recoil.

The nearer the muzzle it is held or rested, the higher it shoots; as it does not allow for the amount of " flip " of the barrel at the time of the explosion.

In rest shooting it is sometimes quite difficult to get your sights adjusted to shoot exactly to the spot—especially with open sights—as some times the change is so small that the adjustments on the sight will not allow it; but such a change would make quite a little difference up or down in a string of ten shots If you were shooting "string measure."

You can generally remedy so small a change by sliding the gun a little farther forward or backward on the rest, as the case may require.

This is more satisfactory and reliable than trying to change position or pressure in holding —a point one should pay strict attention to, practicing regularity whenever shooting.

The pulling of a trigger, while a very important point, seems to vary considerable among shooters, and each one has his own Idea in regard to it.

Many people—especially nervously inclined ones—pull all at once, or " snap shoot " by hit ting or pulling the trigger suddenly and hard enough to set it off, holding their Angers still and away from the trigger until ready to pull. Others keep moving their finger on and off the trigger very rapidly and very lightly until it comes just right, when they hit the trigger an extra hard tap and set it off.

More, however, lay their finger firmly on the trigger and pull gradually by simply squeezing the hand together, and do not know at just what instant it Is going. I generally prefer this way myself and hardly ever try any other pull-off, but have found that at times I could do better for a short period by " snapping."

I have achieved quite a help to my pulling by putting a small cork on my trigger; this gives more pulling surface to my finger, allowing the use of a harder and safer trigger pull, and at the same time appears to require but a very light effort, owing to the pressure on the finger being distributed over so much more surface. There are quite a number of others using it now and they seem in most cases to find it a benefit In their shooting.