The Newton-Pope Rifling and the Oval Bore.

By Charles Newton

American Rifleman, vol 61, No. 22, Feb 22, 1917 – pages 423-424

WHEN we call it the Newton-Pope we do not do so because we designed it, merely because we adopted it and use it in our rifles. In designing our rifle one of our basic principles was not to adopt or discard any idea merely because it was new, or merely because it was old; to test each proposition solely upon its merits and not by the length of its whiskers. Both the spitzer point bullet and the so-called “Ross copper tube" were used by Colonel Jacob, of the British East India Company's forces, over sixty years ago, yet they both pass as new now. Therefore age is no test.

Our rifling is old. The principle was applied by Metford about 1866, and he undoubtedly got the idea from Boucher, who used the same system and described it in a book ten years before that. There fore we are completely foreclosed from any claim of novelty in origination.

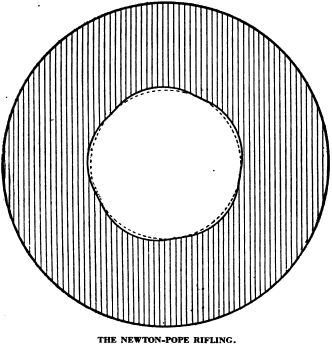

The accompanying cut illustrates the principle of the system. Instead of the barrel being cut with grooves having their bottoms concentric with the bore of the rifle, and forming sharp angles at the sides, the groove is merely a segment of a circle having a shorter radius than that of the bore. This leaves the edge of the groove forming a very obtuse angle with the top of the land and makes cleaning far easier, as both scratch brush and wiping rag bear uniformly upon all parts. It is this ease of cleaning which first attracted us to this type of rifling. Upon further acquaintance with it our respect for it deepened.

The Metford rifling, which is of exactly the same type, was brought out for black powder rifles using cast lead bullets. It required but two years for it to completely revolutionize rifle construction in England, sending the theretofore triumphant Whitworth system to the scrap heap, and it has since been, and still is, to the present day, the favorite rifling for the long range match rifles used by the English target shots. The majority of the rifles used at the last Bisley meeting, in 1914, were rifled on this system.

Being originally brought out for the cast lead bullet, naturally it was given such form as would best adapt it to meet the obstacles to be overcome, including the stripping of the bullet, and the accumulation of fouling in the bore from the inferior grades of powder then in use. To guard against stripping Metford used sometimes seven and sometimes nine or eleven grooves, with very narrow lands between. The lands could take care of themselves. To guard against the accumulation of fouling the grooves were made very shallow. The combination was a winner.

When the British first adopted the .303 rifle they likewise adopted the Metford system of rifling. They did not, however, stop to consider that conditions had changed when they provided their bullet with a cupronickel jacket and drove it forth with the hot gases of cordite. They clung to the shallow groove and narrow land, using seven grooves, although the danger of stripping had disappeared with the application of the metal jacket, and the fouling went with the black powder. As a result of the narrow land, which was attacked by the terrifically hot gases of the cordite not only at the top but upon both sides as well, and the insignificant height of the land, due to the shallow groove, the rifling proved to be rather short lived. To obtain greater length of accuracy life of the barrel, instead of reducing the number and increasing the depth of the grooves, thus giving greater width and height to the land, they abandoned the Metford rifling for the Enfield which possessed these qualities, and the Lee-Metford was supplanted by the Lee-Enfield.

In 1902-3 our ordnance department experimented with a rifling which is described in the official reports as an oval or elliptical bore, the major axis of which was .308 inch and the minor axis .300 inch. It was submitted for test by a citizen, hence an object of suspicion. A single barrel for the Krag rifle was submitted and it promptly outshot the service barrel, both as to velocity and accuracy. The board in charge of the tests then had made a dozen barrels of each type, and the oval decidedly beat out the service style. The board was enthusiastic and ordered five hundred barrels of oval bore made for a service test, when suddenly down from headquarters came orders to discontinue all further tests and return the barrel to its owner. Some of the tests had been made with the then new .30 U. S. G. cartridge, model 1903.

Later, when erosion was troubling the official soul, owing to the adoption of the model 1906 cartridge, another test was made and it was learned that with an 8-inch twist the “oval” bore outshot the service barrel, from soup to nuts, in an endurance test, while a 10-inch twist oval bore was less accurate at the beginning of the test but finished equal in accuracy to the service barrel. It did not occur to the learned Board, who incidentally in this test confined it to a single barrel of each type, that the difference was due to the slip permitted by the melting of the core of the higher velocity 1906 bullet from the friction against the barrel, so the downfall of the “oval or elliptical bore" was complete. The results of these tests may be found, by those interested, in the reports of the chief of ordnance for 1902, pages 223 to 231 and for 1905, page 85.

When we came to manufacture high power rifles, naturally we were interested in making them as perfect as possible. Likewise we were interested in anything which would make the smaller calibers of high-power rifles easier to clean. We -were familiar with the Lancaster oval bore, which is a true oval, and we had used for some years a .333 Jeffrey Mauser, cut with the seven groove Metford system, and which cleaned very easily indeed. We were familiar with the government tests above mentioned. We were familiar with the love of the soldier -for cleaning his rifle; we had “been there and helped skin ’em." We were struck by the fact that none of the army boards had given a thought to the greater ease of cleaning the barrels. Army officers do not clean rifles.

Therefore our first step, when we came to equip our barrel department, was to purchase from the arsenal the identical rifling head with which those “oval bores" were made, and one of our many surprises in the gun business was when we opened that box. Instead of finding a cutter which would make a true oval bore. We found one which cut merely a segmental groove, very little wider than the ordinary groove. The cutter head was exactly the same as the regular head used for the service barrel except that the cutter boxes obliqued against instead of with the twist, and the cutters had the corners rounded off. We had purchased a rifling machine designed by Harry M. Pope, and Harry came up to set it up and get us going. We lost very little time in getting after that rifling head.

The government rifling heads each carry two cutters, on opposite sides, and cut the two opposite grooves at once. The head is drawn through, cutting in two grooves, then returned, the barrel given a quarter turn, and the next draw cuts in the other two grooves. The third stroke cuts in the first two grooves and so on until the grooves are sufficiently deep. This head operated in the same way, and by omitting to rotate the barrel between cuts we cut the first one, a two groove segmental rifling, known to the ordnance department as an "oval or elliptical bore." This barrel was chambered for the .30 Newton cartridge and tried out. It seemed to shoot steadier than the regular barrel.

Next we attached the rotating mechanism and cut, with the same rifling head, a four groove segmental barrel and the lands left after landing the extra pair of grooves were amply broad. This barrel was likewise chambered for the .30 Newton cartridge, which by the way is some stiff for rest shooting as it hands out a wallop of 3,445 foot-pounds, mounted in a rifle which weighed complete 7 ¾ pounds, and taken to the range for test on the German ring target at 200 yards, muzzle rest. Pope kept in the 23 ring, measuring 4 ½ inches in diameter, and the writer kept in the 22 ring, measuring 6 inches. All shots fired were below the center of the target, which indicated that the groups were smaller than the ring diameters. Several were shooting, so it was impossible to preserve the groups. However, we were all satisfied with the four groove segmental rifling, except Mr. Pope.

Mr. Pope contended that we should have an odd number of grooves and use a single cutter, that the rifling head might be, when making a cut, backed up by the smooth solid surface of a land instead of by the edge of another working cutter; that a smoother, better cut can be produced that way. Owners of Pope barrels will notice that they were all cut with an odd number of lands; this is why. He may be right, but it requires five strokes of a rifling head to go once around a barrel as against two strokes by the government method, thus takes 2 ½ times as long to rifle a barrel.

We then employed Mr. Pope as superintendent of our barrel department, and instructed him to make the best and most accurate barrels he knew how. We gave him a free hand as to methods to be used arid as a result we were soon fitted out with index plates for cutting five/groove ‘barrels and those alone, and every day, Mr. Pope may be seen in our factory overseeing a gang of men busily turning out five-groove segmental rifle barrels, call them oval, elliptical, Boucher, Metford, or what you may. We call them "Newton-Pope”

Of course barrels cut on this system, like any other barrels, regardless of how well they are constructed or how accurate they may be, can be ruined in a very few minutes if one deliberately and intentionally sets about the task of ruining their shooting qualities. Any man with but a smattering of knowledge of rifle shooting can take the most accurate barrel ever made, by Pope or any one else, and in a very brief time so injure it that it will spread a group of shot all over a magazine article at the shortest of ranges. It does not require much genius to fix the finest chronometer ever built so it will not keep time. Rifle barrels as well as chronometers are made to use, not to abuse, and the test of merit is what they will do when properly used, not what they will do when neglected or deliberately misused.