Cocking Piece Sight

Arms

and the man, Volume 69 from Google Books

Vol 69, no. 8 - Jan 1, 1922, page 10-11

HUNTING SIGHTS by Major Townsend Whelen

(Continued from page 4)

...it at least 15 minutes earlier in the morning and later in the evening, and every hunter knows that these are the times that game is moving.

When I came back east from this trip I approached the Lyman Gun Sight Corporation on the subject, and the consequence was we got up together the first so-called bolt sight for the Springfield. I wanted the original sight near the eye, but I also wanted accurate and positive adjustments, both elevation and windage, reading to minutes of angle, which the original Lyman did not have. The result was the first Lyman No. 103 sight. It was well made in the Lyman tool room by a tool maker. Every part fitted perfectly, and to this day this sight has remained tight and accurate. Based on my experience with this sight I recommended the No. 103 most highly-—and thereby got myself into a lot of trouble. Theoretically the sight is an ideal one in a number of ways. You have the original Lyman, near the eye, and yet it flies away from the eye as the rifle is fired, hence can be used on rifles of heavy recoil. It has the proper adjustments for elevation and windage. I can not imagine a better sight than the original which was made for me, but please notice that it was made by hand and by an expert toolmaker. In regular production the sight has not been the success that I hoped it would be. It is a hard sight to produce by machinery without it sooner or later developing looseness and lost motion within itself. The cocking piece is not a very secure or constant place to mount it. Some cocking pieces on the Springfield develop a looseness all of their own, and some of them vary their position when the safety is on or off. The position of the sight interferes with a firm grip of the small of the stock so essential to good holding and proper trigger squeeze. The Lyman people have lately slightly redesigned this sight in an effort to correct the looseness which often develops, and I hope they succeed, but they can hardly stop the vagaries of the cocking piece or the interference with the grip of the right hand.

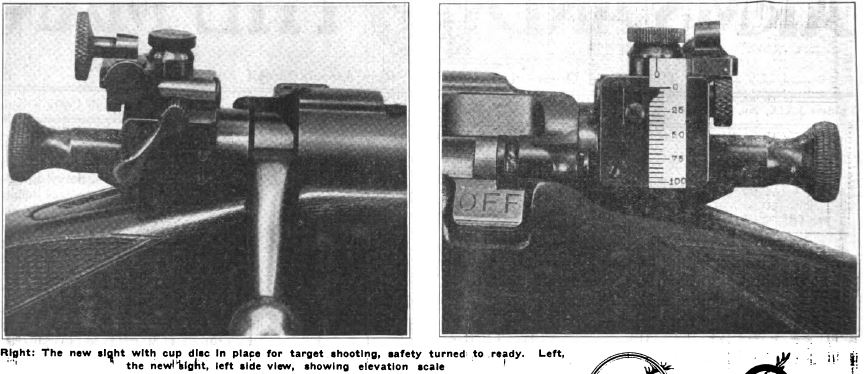

NOW, the sporting Springfield is such a superb hunting rifle that it seemed a darn shame that there was not a superb hunting sight to go with it. So I determined to see if I could not make one. I wanted the original Lyman principle of a large aperture and small disc near the eye, and I wanted all the positiveness, accuracy and strength of the adjustments as seen on the Lyman No. 48 sight. The sight must be securely mounted on the rifle, it must not interfere with the grip, and there must be absolutely no looseness in either the sight or its mounting. It must be strong and sturdy like the Lyman No. 48. After a lot of thinking over I evolved an idea in my mind, and then carried it out with the assistance of Mr. James V, Howe who is first and foremost a most excellent tool maker, and next a most enthusiastic rifleman and amateur gunsmith. The result is shown in the accompanying illustrations, an as amply justified all the time and labor put on it. First we found that in order to get the original Lyman principle of aiming with the front sight alone the aperture had to be three inches nearer the eye on the Springfield than the Lyman No. 48 aperture was placed. Obviously the place to put it was on the sleeve as it was not only in the right position, but the sight placed here would not interfere with the proper hand grip on the small of the stock. But the sleeve on the Springfield has a little movement all its own and is not a secure place to mount a sight. Also there is no place on it where the sight can be securely set. So we designed and made an entirely new sleeve. and this in turn necessitated making an entirely new form of safety. It will be noticed that the new sleeve is of such form that it makes an excellent base on which to place what is Practically a Lyman No. 48 slide.

The top of the slide is bent a little to the rear so as to bring the aperture a little nearer to the eve. otherwise it is essentially a Lyman No 48 slide placed on the left side instead of the right. Placing it on the left made it much easier to adjust and easier to see the graduations. It was necessary to assure the slide coming to absolutely the same place with reference to the receiver every time the bolt was opened and closed if the sight was to come to a constant position with respect to the front sight and barrel for every shot. We found that the tendency of the sleeve was to rotate slightly to the right, so on the under side of the sleeve and to the right of the cocking piece groove we placed a stop pin which abuts against the top of the tang of the receiver. On the opposite side of the under portion of the sleeve we placed a spring plunger which every time positively forces the sleeve over to the right to an absolutely constant position. When the bolt is closed the sleeve and entire sight is forcibly pressed to a constant place with reference to the receiver, consequently it is in exactly the same position for every shot. We improved the adjustments considerably by engraving the words “Up” and “Down” on the head of the elevation screw to show which way to move it to get the desired change in adjustment, and by putting “R” and “L” on the windgauge and windgauge screw to designate right and left windage, in each case with arrows pointing to show the direction to turn.

The matter of the safety lock was quite a problem, but we finally solved it most excellently by cutting a circular notch in the top of the cocking piece inside the sleeve, and making a half-round bolt to go through the sleeve from side to side and engage in this notch and very slightly cam the cocking piece back when it was turned to safe. When turned to “ready" the bolt presents its flat side towards the cocking piece and does not interfere with its moving forward. This positively locks the cocking piece and firing pin back so they can not fire the cartridge, but it does not lock the bolt from opening, which was not regarded as at all necessary. Notice the thumb piece on the right side of the sleeve which works the safety. When the rear half of this thumb piece is up the rifle is safe and can not be fired. To turn it to “ready" bring up the thumb and push it down, just exactly as though you were cockin2' a hammer rifle. The operation is simple, easy and natural. It can be done as quick as lightning, and is a great improvement from the hunting standpoint over the regular military safety on this rifle which takes time and effort to turn. The safety makes practically no noise as it is operated. There is only a hardly discernible click which will not alarm the game. Nevertheless we made the thumb piece double for two reasons-first, so that the hunter could grasp it between the thumb and forefinger and turn it over slowly and without the slightest noise, and also so that he could operate it easily if a little dirt should get in it, or a little frozen snow, or if he had on thick gloves.

1 have had this sight on my rifle now since last July, and have given it a most thorough trial. It fulfills in a. most perfect manner every one of the requirements of a hunting sight as laid down at the beginning of this paper. It is as accurate as any sight ever made. I have been unable to find or imagine any way in which it could be improved for use on the Springfield, except that if it were made up regularly for the market ‘I think it would be well to have it made so that the aperture takes normally a slightly lower position so as to admit of its being used with a slightly lower front sight than the regular military height, an advantage from a hunting point of view. It is a very expensive sight to make by hand. A first-class toolmaker with a machine shop available would probably have to charge about $250 to make one, but we have estimated that it could probably be made by machinery in lots of, say, 500 to sell for somewhere between $15 and $20. On this account it will never be a popular Sight if it is ever made for sale, but will rather be the best hunting sight for those who know the value of a perfect sight and are willing to pay the piper. I do not know if it will ever be manufactured. It depends of course upon the demand. Mr. Howe and I have placed nothing in the wav of its manufacture. It is probably covered by the patents issued on the Lyman No. 48 sight, and it is also perhaps likely that the Lyman Gun Sight Corporation might consider its manufacture if they could see a sufficient demand for it to justify their undertaking it. At any rate I am perfectly satisfied with it.

Vol 69, No. 10 – page 12

Cocking Piece Sights

BY VAN ALLEN LYMAN

With regard to sights mounted on the firing pin or cocking piece of a bolt-action rifle I would rise to remark that, broadly speaking, they are a “frost” and had better be left alone for serious work, unless one merely wishes to experiment with them out of curiosity. Then, for the love of Mike, do the experimenting long before you go in the game fields. You may change your mind, and want to make a change.

I am aware that this rather strong statement may call forth denunciations from many who have used such sights for years with perfect satisfaction and who prefer them to any other kind for the bolt action rifle. The fact remains, however, that, taken all in all, the cocking piece sight has not given general satisfaction to date, and the best proof of this is that, though it has been generally known for a long time, it is comparatively little used. From an optical point of view it has decided advantages over the receiver sight, and if it were as mechanically satisfactory it would have superseded the receiver sight long ago. The principal objections to the cocking piece sight are that it can not be depended on to keep in perfect alignment, and it is mechanically weaker and more liable to in jury than other types of sights. Also, it adds weight to the firing pin and renders it more sluggish in its action, though this may be more of a theoretical than a practical objection.

With a desire to get first-hand information on the subject (which is being passed along to fellow shooters for the reading), the writer once had a Lyman No. 103 sight fitted to a Springfield firing pin--a factory job. The sight was nicely fitted to the cocking piece, but when the gun was cocked the aperture would wobble sideways for nearly a sixteenth of an inch, due to natural looseness in the bolt mechanism clearances. Presumably all this looseness would disappear when the trigger was drawn, for, as a well-known rifleman said to me when explaining the virtues of this sight, “the bolt and all its parts will always settle down to the same place each time as the trigger is drawn, and naturally the sight comes to the same place, too; so any looseness in the first place is immaterial.” Did it do so? It positively did NOT. I know for a fact that his sights so rigged did exactly what he claimed for them, but his were super rifles, made pets of and hand finished with an expert's care and not the general run of factory stuff that Mr. General Public has to accept, and this also should be borne in mind.

The logical thing to do was to “make the fix” so the sight would come to the same place each time, and a couple of evenings were spent in grinding and polishing and working on the trigger mechanism. This did the work, almost. As the trigger was pulled the sight would come right to the same place each time, almost. But that “almost,” proven by a middle sight on the barrel, showed that the sight drawing down to exactly the same place every time was non-existent, at least on that particular rifle. Hope was not given up, however, and an attack was made along another line, that of tightening up the bolt mechanism all through so as to take out every bit of wiggle.

Space does not permit of telling in detail how this was done; suffice to say that the general procedure was to make every thing a few thousandths of an inch too tight and then dress down with fine emery cloth. The final result was a rifle having a firing pin with absolutely no shake to it at all, and incidentally a pretty stiffly working bolt in consequence. There was no play to the sight at all this time; it shot finely, as good as a No. 48 receiver sight would have done in the first place and with the added advantage of being close to the eye. But after a moderate amount of shooting had been done it was found that the sight was loosening up in the dovetail groove where windage adjustment is made. This was apparently caused by the unavoidable yank and shock that is necessarily given to the sight when firing. Taken all around, it didn’t work out in as satisfactory a manner as had been hoped for, and I knew then the reason for those occasional advertisements in the sporting magazines—somebody wanting to trade off a cocking-piece sight for one of the other kind.

It must be borne in mind that the fore going was with a Springfield rifle which has the notch and trigger cut squarely across. The writer once had a Newton rifle fitted with a firing pin sight and this sight gave good satisfaction for hunting after it was fixed up. In passing, it might be said that it was about the only thing about the rifle that did give satisfaction. This New ton rifle had the sear and the notch, both cut on a decided bevel, so that the tendency of the firing pin when cocked was to slide forward on the sear as far as possible, the resultant effect being that it tended to rotate always in one direction (it could not, of course, actually rotate, but it tended to), and at the same time sliding forward came to rest, jammed, if you will, in the same position every time or very close to it. The sight, being attached to the firing pin, naturally came to the same position also, or rather did after all looseness in the sight itself, for it was originally a shaky thing, had been removed.

This scheme of cutting both the sear and the notch it engages in on the bias, so that when cocked and under pressure of its spring the firing pin will always tend to slide around and jam into the same position, is, so far as the writer can see, about the best arrangement if a man really wants a cocking-piece sight. The objection may be raised that this might afflict the trigger pull, but it does not seem to. What actually happens is, that if part of the sear and notch is ground away to get the bias effect, when the rifle is cocked the firing pin is further forward than it was when the notch was square across. In some rifles this will make a difference in the operation of the arm; with other rifles it will not matter.

May 1, 1922, pg 11

A Defense of the Cocking Piece Sight

By WALTER B. WILSON

In the February 1 issue of ARMS AND THE MAN Mr. Van Allen Lyman arose to remark that sights mounted on the cocking piece of bolt action rifles were, broadly speaking, a “Frost” and had better be left alone for serious work. Broadly speaking, I share in his belief, although, in at least one case of a Lyman sight on the cocking piece of a Springfield, it is not a “Frost," but, on the contrary, is a

most satisfactory arrangement and does return to absolutely the same place each time, with relation to the receiver every time the gun is cocked and the trigger drawn.

This particular Springfield, however, happens to have the most finely adjusted and smoothest working bolt and trigger mechanisms that I have ever seen on a bolt-action rifle, and since the present owner has had this rifle he has still further generally dolled up the workings by polishing with dimantine the bolt and bolt well, all cam surfaces, lug races, etc., beveled the cocking nose and sear and made various other adjustments, until there is no unnecessary drag or looseness in any detail, and this cocking piece does not “almost” return to the same place each time, but it does positively.

The writer has seen bolt guns with sights on the cocking-piece, that did, as Mr. Lyman has said, “return to the same place each time—“almost.”

Mr. Lyman closes his interesting piece on “Cocking Piece Sights" with the statement that his next attempt to fix a cocking—piece sight would be made by using a sight of the Marble flexible joint sort, changed over for use on the cocking-piece, and this statement gave me what I believe to be a good idea.

The next morning after reading his article I went to work to make a sight base which would receive a Marble upright and joint. This base was carefully made by hand of tool steel, and when it was finished the Marble mechanism fitted nicely. I happened to have a Marble sight with an up right and stem of just the right length to use in connection with the base and the cocking-piece of a Springfield.

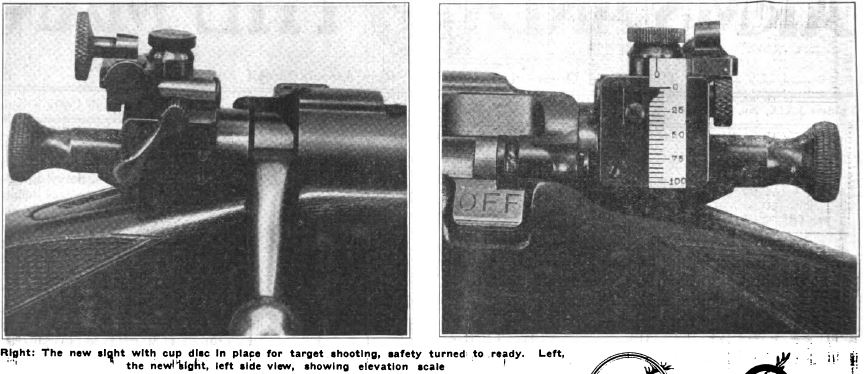

There are shown herewith some crude drawings which represent an attempt to illustrate this sight.

I believe this sight is going to prove to be the real thing for use on the firing-pin of a bolt-action hunting rifle. One can yank his rifle through the thick brush all he pleases and if he happens to bump the rear sight in so doing he will not find when he jumps that nice big buck, that his rear sight is broken off because it was locked, or else folded down against the tang because it was not locked; but she's right there where he wants her to be, and if he fails to get in a shot at that buck it will not be because his sight was in the wrong position when he jumped.

May 15, 1922 page 15-16

Aperture Sight for the Cocking Piece

By VAL A. FYNN

IT is universally conceded that an aperture rear sight should be as near the eye as possible and that, in a bolt action rifle, the ideal location of such a sight is on the cocking piece. Unfortunately the cocking piece is movable when the arm is cocked and the position of any rear sight attached to it is therefore indefinite. Since with a 30" sight radius a displacement of the rear

sight of 1/100th of an inch corresponds to a change of impact of 1.2 inches at 100 yards it is easily seen why such sights have not given general satisfaction. It does not appear that this defect can be eliminated by machining the bolt and receiver to closer limits. Substantially closer limits than now adopted in the best makes of bolt rifles are not practical for quantity production and even if they were all the play could not be taken out and the effect of wear at numerous points would still have to be contended with.

It has occurred to the writer that satisfactory results could be secured with an aperture sight on the cocking piece by providing means for positively locating said cocking piece, and therefore the rear sight, at the extreme end of its travel—when in the full cock position. The very fact that the play introduced by the unavoidable tooling tolerances allows the cocking piece to move practically in all directions makes it easy to positively locate it at any point of its travel without introducing undue friction or necessitating the use of appreciable effort. As soon as the trigger is pulled the cocking piece moves out of engagement with the locating means and completes its travel with no more interference than usual.

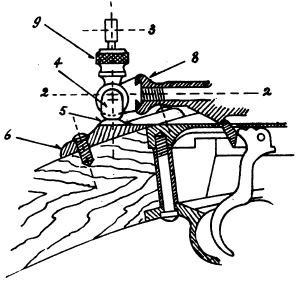

One way of carrying this idea into practice is shown in the accompanying sketch which diagrammatically represents part of the Springfield mechanism with the addition of one form of the means for positively locating the cocking piece. The aperture sight 9, a side view of which is shown, is dovetailed in the usual way into the head of the cocking piece 8, which is at full cock, and a steel skate 4 is rigidly attached to each side of the sight 9 in such manner as to retain constant space relation to said sight. A steel block 6, shown in longitudinal section, is firmly secured to the rearward projection of the receiver and to the stock as indicated by screws in the figure. This block is provided with two humps 5 adapted to cooperate with the skates 4 "and separated by a groove which allows the withdrawal of the bolt and corresponds to a similar groove in the receiver. The cooperating surfaces on block and skates are preferably case hardened and highly polished, in this case they are supposed to be in one plane parallel to the axis of the bore.

The edges of all four surfaces are rounded so as to facilitate engagement and minimize the risk of injury. The humps 5 are preferably so located that the last part of the action of cocking causes the skates to ride up on the humps without however forcing the cocking piece into a position outside the limits allowed by the available play. In this way it is possible to positively locate the cocking piece at the outer end of its travel without subjecting it to a severe strain and without introducing undue resistance against the forward movement of the cocking pin. The locating surfaces should be short in the direction of movement. Because of the sliding engagement the locating surfaces tend to keep automatically clean.

The arrangement of locating surfaces described in connection with the sketch will prevent the cocking piece from rotating about its axis and will positively locate it in a vertical direction but may in some cases permit a transverse displacement when at full cock. To eliminate this last possibility it is only necessary to incline the locating surfaces on the humps 5 to wards each other and to shape the surfaces on the skates in a corresponding manner. Instead of a locating plane we will then have a V-shaped locating groove.

The block 6 can be attached to the tang only and this may be good enough although wood is not a reliable basis to fasten a locating surface to. The next best scheme is that shown in the sketch where the block is attached to the rearward projection of the receiver and to the tang. A better way is to braze the block to rearward projection but the best way of all would be to make the humps 5 integral with the receiver.

It may not be convenient to attach skates, or the like, to a sight as now sold nor may it be possible to provide the locating surfaces on some part of the sight mechanism. In such case it is quite simple to locate by means of flats cut on the knurled head of the cocking piece—independently of the sight mechanism—or on a collar secured to some part of the cocking piece, for instance to its waist just ahead of the knurled head. This is perhaps always the best arrangement since it does not interfere with the construction of the sight itself and also reduces the already small weight of the added parts. In this case a suitably shaped block is preferably brazed to the rearward projection of the receiver on each side of the groove accommodating the sear notch and an inclined locating surface tooled on each block.

Since the line of sight 3 is some distance from the axis 2 of the cocking piece, all displacements of the latter are magnified. It is best to keep the line of sight as close to the axis of the cocking piece as possible and the locating surfaces as far from that axis as may be.

Such a rear sight locating arrangement should be of particular value for the Mannlicher-Schoenauer.