American Single Shot Pistols

BY HENRY WALTER FRY

American Rifleman, vol 68, No 22, Jul 1, 1922 pages 3-5, 9, 10

WHEN the pistol was first designed and for four centuries later, nearly all pistols were made single shot, the exception being a small number of double, and a still smaller number of multibarreled weapons, but in these days when the revolver and the magazine automatic are almost universal among civilized nations, the single shot target pistol. long barreled, accurately bored and rifled, fitted with special sights, with its parts carefully made and highly finished, but slow in loading and extraction, is in a small and select class by itself, like the high-grade smooth-bore flintlock, and later the rifled percussion lock duelling pistol from which it is directly descended.

Dueling in America is now a thing of the past, and even in the Emerald Isle, where it flourished exceedingly a century ago, is no longer practiced. No longer does the Irish gentleman on his death bed give to his son his last exhortation to be “always ready with the pistol.” No longer is the rosewood or mahogany pistol case, containing the family duelers “Sweetlips” and “Darling” handed down as a precious heirloom from generation to generation, and children are no longer carried out to the dueling ground and held up in nurse's arm, “to see papa fight.” Skill with the pistol in those heroic days was part of every Irish gentleman's education, and of a young man entering Irish county society, two questions were always asked, namely: “What family is he of?” and “Has he ever blazed?” Dueling was especially prevalent among gentleman of the law, and one author, writing of the customs of those times says: “Among the members of the Irish bar the list of killed and wounded was very considerable, and to a young lawyer with his way to make, a case of pistols was thought to be more useful than a shelf full of law books.”

The same author relates some very dreadful tragedies resulting from the practice of dueling; one of them being the death of his own brother. Even the history of the country, in which the number of duels fought is comparatively small, is not free from the record of the untimely deaths of those who could ill be spared from their country’s service. Who, for instance, can measure the loss to America in the prime of his career of such a states man as Alexander Hamilton, and it is by no means unlikely that American political institutions may still be suffering from the loss inflicted upon them by Aaron Burr’s pistol, a hundred and seventeen years ago. We know, too, that a very distinguished American naval officer, Commodore Decatur was killed, and Andrew Jackson, the hero of the battle of New Orleans, severely wounded in duels with the pistol.

As I said, however, the custom, at least among English-speaking peoples, is now a thing the past, and the dueling pistol has been relegated to the public or private arms collection, and its successor, the modern breech-loading rifled single shot pistol is merely the instrument of a very pleasant and agreeable pastime, which may be practiced and enjoyed by people of ages from nine years old to ninety. A very good instance of the latter is given by Walter Winans in one of his books on the pistol, where he tells of a shooting friend so old and feeble that he had to be taken out to the range in a wheeled chair, yet once on the firing point could raise his pistol and place his shots in the bullseye with an accuracy which many a young man might "envy, and only the other evening, on the pistol range of the club to which I have the pleasure to belong, might be seen a marksman of over ninety, shooting the target pistol with all the keeness and enthusiasm of the latest joined members.

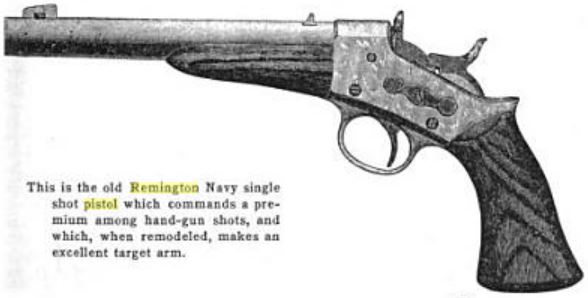

American breech-loading single shot rifled pistols have been made in various calibres from .22 up to .50, the latter being the Remington Army and Navy Models. Why these .50 calibre pistols were made single shot when it would have been perfectly easy to have made a simple, compact five-chambered revolved of that calibre, I for one, quite fail to understand. It would have been no more bulky than a .45 six-chambered weapon. Five-chambered revolvers of .50 calibre were made in England both on the cap and ball and the metallic cartridge system. I have one of the former in my possession made by Deane Adams and Dean .38 gauge (.497 calibre) with 8 inch barrel. The diameter of the five chambered cylinder is 1 ¾ inch as against the 1 5/8 inch diameter of the six-chambered cylinder of the .45 single action Colt, and I actually had the chance of buying in Australia a Tranter's five-chambered revolver taking the .50 calibre Eley revolver cartridge. I'm sorry now that I didn't.

Besides the .50 calibre Army and Navy pistols there were single shot weapons made by various factories for the .44 Russian, .38 Smith & Wesson, .32-20 W. C. F., .32 Smith & Wesson .25 rim fire, and .22-7-45 rim fire cartridges, hut in very small numbers compared with those chambered and rifled for the .22 long-rifle cartridge. We are now dealing with a period from twenty to twenty-five years ago, when there was very much more rifle and pistol shooting done in this country than there is now. At that time there were four well known makes of .22 calibre single shot target pistols. They were made in various lengths of 6, 8, and 10 inch barrels and one maker supplied 12-inch barrels if required, but for target shooting the l0-inch barrel was everywhere recognized as the standard. The four makers were, the Stevens Arms 8: Tool Co., the Remington Arms Co., Messrs. Smith & Wesson, and Mr. William Wurfflein.

Of these four only Smith & Wesson are now making .22 calibre ten-inch pistols. The Stevens Company made quite a variety of models, in heavy, medium and light weight, the heaviest being the Lord Model, named after Mr. Thomas Lord, who at one time had a shooting gallery in New York City. He was a big, powerful man and the pistol named after him had a very long handle suited to a big man’s hand and the weight of the pistol with 10-inch barrel was 2 ¾ pounds and with 12-inch barrel 3 ½ pounds, weights which are very much too heavy for the ordinary pistol shooter, usually a middle-aged man of moderate strength and sedentary habits, to fire many shots with, without his arm getting very tired.

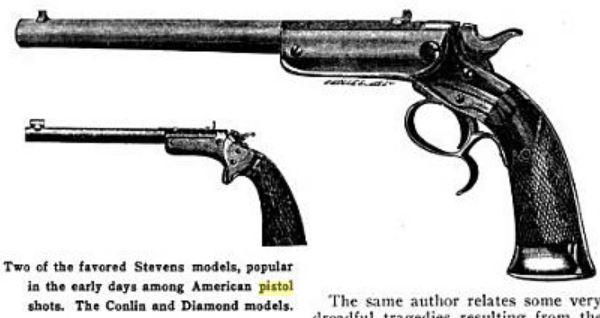

Next came the medium weight pistols, the Gould and Conlin Models, exactly similar, except that in the Conlin Model, named after Mr. James Conlin, also a shooting gallery proprietor, there was a spur on the trigger guard for the second finger, where as in the Gould Model, named after the late A. C. Gould, a well known sporting journalist and author, the finger spur is absent. The weight of both these pistols in .22 calibre and with 10-inch barrels weighed about 1 ¾ pounds.

The barrels, like all those of Stevens make, were very accurate and the lock very simple in design, but inferior in workman ship and material. The locking catch of the break-open action was much too small and flimsy and the barrel would work loose in the frame with only a very moderate amount of wear. Another defect was in the grip, which in the Gould Model was too small in the upper part which is grasped by the fork of the hand, between the thumb and forefinger. On the Conlin Model, with its spur on the trigger guard for the second finger, this was not so noticeable. When the company discontinued making the Lord, Gould and Conlin Model pistols, they put out another, called the Offhand Model, made with barrels, 6, 8 and 10 inches long with a handle very much like that of the Gould Model but polished instead of checkered walnut, and being made fuller in circumference in the upper part, gave a very much better hand hold.

Altogether the Stevens Offhand Model was not at all a bad pistol for target work when fitted with proper target sights in place of those supplied by the factory, the trigger and sear hardened, and treated with a fine oilstone to give about a 2 ½ lbs. pull. Why the company, instead of devoting themselves to improving the material and finish of the lockwork and fitting the ten inch size with the "Partridge" pattern sight, which a little inquiry would have shown them to be the favorite of all target shooters, should have left off making the Offhand Model and have gone to the trouble and expense of designing and manufacturing such a weapon as their present No. 10 pistol passes, my comprehension. I can only attribute it to the curious perversity with which all the American arms companies are, without exception, occasionally afflicted, and which makes them sometimes discard the good in favor of the bad, the bad for the worse, and the worse for the absolutely unspeakable. The No. 10 pistol has two and only two good points; it has a good handle and the Partridge sights, but the barrel is only eight inches long instead of the ten, which every target shot insists on, and instead of the light, smooth working hammer which years, I had almost said generations of use, have accustomed him to expect, there is a stiff, ugly little cocking piece with a small, sharply milled head apparently made to give the unfortunate user of it a sore thumb and forefinger.

My advice to the Stevens Co. would be to relegate that particular model to its proper place, the junk pile, and to bring out a special Offhand target model with ten-inch barrel, Partridge sights, a larger and stronger locking catch, lockwork of the best material and finish, easy, smooth working mainspring, trigger pull carefully hand adjusted to 2 ½ lbs. and an extractor which will draw the fired shell clear of the chamber. Then they would have a pistol which the man who devotes himself to fine target shooting would think worth investing in. He certainly does not regard the present No. 10 pistol in that light.

Another model of pistol made at one time by the Stevens Company was a very light one called the Diamond Model, with either 6-inch barrel, weighing 9 ounces or with 10-inch barrel weighing 11 ounces.

Now, though, as sent from the factory they had several serious defects, yet these were both very fine little weapons, and it is to be regretted that they are no longer manufactured. Chambered and rifled for the .22 long rifle cartridge they were both very accurate shooters and two of the best fifty yards scores, counting each 99 out of a possible 100, were made with a 10-inch Diamond Model pistol. But this model, being so very light, was very difficult to shoot with, most men preferring one of medium weight from 1 ½ to 2 lbs.

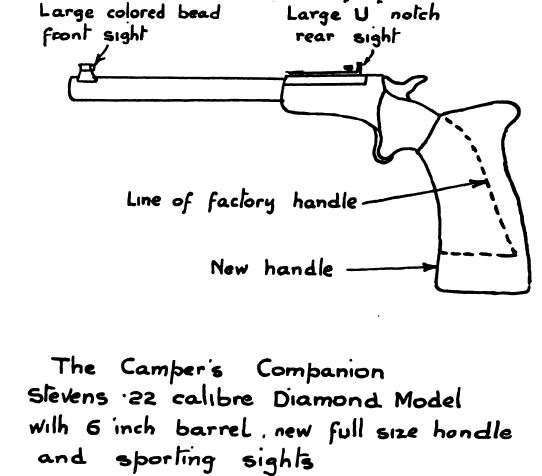

Its defects were several. As in the other models the material and finish of the lock work were poor, and the mainspring and trigger pull often very stiff and hard. The design of the guardless trigger was obsolete, and the handle so small that it was about suited to the hand of a five-year-old child, and not to that of a full-grown man, the makers of it seemingly ignorant of the fact that the human hand is not capable of automatic shrinkage to suit this particular size of handle. In spite of these defects, all of which can be easily remedied by any one who is something of an amateur mechanic, fitted with a proper sized grip, the mainspring and trigger pull eased down to a comfortable working strength and fitted with a large white or colored metal bead front sight and large U rear sight, these little arms make admirable weapons for shots as birds or small game when on a hunting or fishing trip; or even for practice at tins and other miscellaneous objects on a walking or camping tour. The little 6-inch Diamond Model, in particular, is a wonderfully powerful and accurate little pistol, and so light that it may be carried all day long in the pocket without the weight being noticed at all.

If only the Stevens or some other company would make a line of these extra light pistols with good grips, improved triggers, easy trigger pulls and mainsprings, sporting sights, such as I have described, and with either 6, 8 or 10 inch barrels, I believe they would have a ready sale among the large and increasing number of those who take their vacations in the form of hunting, fishing, walking or motoring camp life in the great outdoors.

Only one model of single shot target pistol was made by the Remington Arms Company, by fitting a ten-inch barrel with target sights on to the frame and action of the .50 calibre single shot Army Model pistol, that having a better grip than that of the Navy Model. A few were made with 12 inch barrels and Mr. A. C. Gould, author of "Modern American Pistols and Revolvers," has recorded a series of trials at long range with a pair of .32-20 Remington pistols with 12-inch barrels, but in the 1904 Remington catalogue, ten inches is stated as the only length of barrel supplied, and chambered either for the .22 short, .22 long rifle, .25 Stevens rim-fire, or .44 Smith & Wesson Russian central fire. It was the only one of the four makes of target pistols which had a fixed barrel, the other three having break-open actions and the downward hinging barrels. The Remington pistol was made with the rolling block action with which the Remington military rifles were fitted but of smaller pattern. I had the good fortune to acquire a few months ago a Remington target pistol in practically new condition with 10-inch barrel and chambered for the .22 long-rifle cartridge. The rifling has very shallow grooving and is bored exactly right for the bullet of the Winchester Precision .200 cartridge, which is of a shade smaller in diameter and of rather harder metal than that of other makes. The pistol is wonderfully accurate and more than once firing it from the six-point rest at 50 yards I have succeeding in making groups, all ten shots of which would have touched a one-inch circle and several more of which nine out of the ten shots would have struck a quarter. Its two defects are, first, that the hammer is a little too heavy, a small light hammer, the fall of which will explode the cartridge without jarring the muzzle out of line, being essential to the perfect target pistol; second the weight of the pistol, 2 ¾ lbs., makes it too heavy for the arm of the average man, but both these defects can easily be remedied by cutting out all unnecessary metal from the hammer and having about 3/16 inch turned off the outside diameter of the barrel. The other day I saw and handled a Remington .22 calibre pistol which had been altered in this way, to the immense improvement of its weight and balance, making it a perfect target weapon. The popularity of the Remington action for target pistols in shown by the fact that all over the country .50 calibre Army Model weapons are being bought up for conversion to target arms and the last time that I was the in the shop of Peterson of Denver I saw no less than four which had been sent in for conversion to .22 calibre.

The Smith & Wesson Company is the only one of the four makers which I have named which is still manufacturing a ten inch .22 calibre target pistol, and at the present time I suppose that there are more Smith & Wesson pistols now in use by target shooters than those of all the other three makers put together.

And yet the Smith &: Wesson single shot is, strictly speaking, not a pistol at all, and when I say that I mean that, from butt to muzzle, it has not been designed as a single shot pistol pure and simple, being, as it is, a curious nondescript makeshift of a single shot barrel and extractor joined on to a revolver frame and action and with the small revolver stock replaced by one giving a longer and fuller grip to the hand. In fact, at one time one could buy a case containing combination set of pistol and revolver parts which would be made up to form either a five-chambered pocket revolver taking the .38 S. & W. cartridge or a single shot pistol 6, 8 or 10 inch .22, .32, or .38 calibre barrel. The revolver action to which the single shot barrel was made to fit was that of the single action model 1891, and this single action target pistol is preferred and sought after by the target shots in preference to the later double action model now being made by the Smith & Wesson Company.

It was made in three calibres, for the .22 long-rifle, the .32 S. &: W. or the .38 S. & W. cartridges and with 6, 8 or 10 inch barrels, but the larger calibres and shorter lengths were but little used in comparison with the ten-inch .22 calibre size. About a year ago I was lucky enough to find in the sporting goods store of a little country town one of these ten-inch .22 calibre 1891 Model pistols in perfect condition, and to those of my fellow pistol shots who wish to find one of these old model pistols I would recommend them to visit the sporting goods stores of all the country towns of from two to ten thousand inhabitants within their reach, and it is quite likely that they will succeed in discovering one, which, like mine, has perhaps been in stock for perhaps twenty years and more.

The two principal faults of the Smith & Wesson pistol are the barrel locking catch, which, though beautifully fitted and of very neat and compact design, is a little more awkward to operate than that of either the Stevens or Wurfflein pistols and the handle, which, like those of the Stevens pistols, is too small in the upper part and is set on the frame at too sharp an angle with the center line of the barrel. This, by the way, is a fault common to every American revolver of modern design, without exception.

The effect of this particular fault in the Smith & Wesson pistol and also all modern American revolvers is that when held in the way. necessary to bring the first finger on to the trigger there is an unfilled space left between the upper part of the second finger and the under side of the frame, where it curves down into the trigger guard, the top of this curve being level with the line of the frame above the trigger instead of being below it, as it is in the Stevens, Remington and Wurfflein pistols. In the Remington pistol especially the under side of the frame slopes sharply downward toward the stock and it is this, together with the fullness of the grip at the part fitting between the thumb and first finger, which gives the handle of the Remington pistol that solid, comfortable feel in the hand which is so essential in a pistol with which a shooter expects to do fine and consistent shooting. It is the combination of these two features which makes the grip of the old single action Army Colt, designed more than seventy years ago, superior to that of any of the later models of the Colt revolvers.

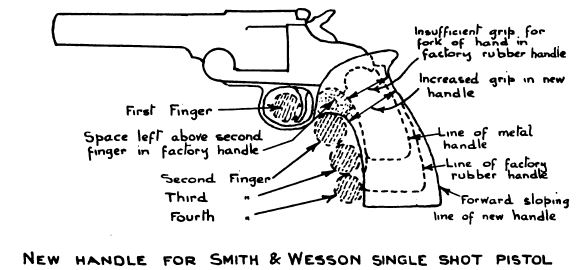

The defect in the size and shape of the Smith & Wesson pistol may be easily remedied by making a special stock, something on the lines of that shown in the accompanying sketch. I have made and fitted one to my own 10-inch Smith &Wesson, but claim no credit for the design, as my pistol handle is simply a copy of others which had been made by several of the members of the Manhattan Rifle and Revolver Club, to which I have the honor to belong. It will be seen that the grip curves away from the lower part of the trigger guard and that it rests solidly upon the upper side of the second finger, the space which the factory handle leaves above it having been filled up. The increased size of the grip between the second finger and the fork of the hand insures a firm, comfortable grasp, while the forward sloping lines of both the back and front of the stock tend to give the whole hand a downward bend, and to bring the first finger to the lower end of the trigger where there is the greatest amount of leverage.

My new handle has made my 10-inch Smith & Wesson as near a perfect target pistol as anything can be, it's accuracy, beauty of outline, smooth and easy working and perfection of workmanship and finish make it a weapon which it is a renewed pleasure to handle every time that I take hold of it, and I cannot help thinking what a pity it is that this old single action model was superseded by the present double action pattern, which, though a very fine pistol, as being a Smith & Wesson it is bound to be. is not in the working of its lock action, quite the equal of the older model and the fact that I know several expert shots who are keenly on the look out for a chance to buy one of the old single action confirms me in my opinion. Two other good points in the make up of the Smith & Wesson pistol are, that the weight, about 1 ½ lbs., is just about suited for men with only moderate strength of wrist and arm, and at the same time it has weight enough to insure steady hold and not too much recoil, and the extracting action, which draws the fired- shell completely clear of the chamber. In the Stevens, Remington and Wurfflein pistols, the extractor only draws the shell part of the way out so that it has to be pulled out the rest of the way by the thumb and forefinger. In the barrel a combination of lightness and strength is effected by a hollow rib along the upper side, which enables a light and slender barrel combined with the maximum of stiffness to be used.

There are not very many of the pistol shots of the present day who have handled or seen a Wurfflein pistol, and I suppose that to most of the younger ones its very name is unknown. That is not very strange, as it was not made in large numbers, Mr. William Wurfflein of Philadelphia, furnishing most of them to order and to any calibre that his customer desired. And yet it was a weapon which had several very good points about it. It had an excellent handle, more like that of the French duelling pistol than any other pistol of American make a break-open action with a very strong and solid locking catch and more conveniently operated than that of either the Stevens or Smith & Wesson pistols. It was accurately bored and rifled and with a .22 calibre Wurfflein pistol with 10-inch barrel, which I was lucky enough to purchase in almost new condition some time ago, I have, from the six-point rest placed ten shots in a space 1 ½ x 1 ¾ inches at 50 yards. But it is a very heavy weapon, weighing fully 2- ¾ lbs., with most of the weight in front of the shooter's hand and a lot of unnecessary metal in the barrel and frame which makes it not merely heavy, but muzzle heavy and clumsy and the mainspring rather too stiff and hard. It has, however, in it the makings of a good target gun and with the unnecessary metal cut away from the barrel frame and hammer, and the main spring eased down a bit, would make a very satisfactory arm for anyone who had a fancy for a pistol of break-open pattern with a really good grip and strong and easily worked locking arrangement. Wurfflein pistols have not been made for many years, and are now so scarce that they are now quite a curiosity to the present generation of marksmen.

There is one other single shot target pistol of American make which was not manufactured in great numbers and which is no longer on the market, and that is the ten inch .22 calibre Hopkins & Allen, which was built very much on the lines of the 10-inch Smith & Wesson, but with a different form of locking catch and a very much better form of grip. At one time I was the owner of a Hopkins & Allen pistol but disposed of it before leaving Australia. It was strong, well made, and accurate, but the workmanship and finish were not quite of the superlative quality which is the distinguishing mark of the Smith & Wesson productions and in this country have never even seen one.

The only other American single shot pistol of modern design is the Colt Deringer. which was not a target gun but a vest pocket weapon with small grip and 2 ½ inch barrel chambered for the .41 short rim fire cartridge and made for use at close quarters only. This, too, is no longer manufactured. The name Deringer or derringer comes from Henry Deringer, a Philadelphia gunsmith, by whom large numbers of small single barrel cap and ball pocket pistols were made in days gone by. They were usually made in pairs, and many of them were of very high-grade material and workmanship. It was with one of these small muzzle-loading pocket pistols that President Lincoln was murdered by John Wilkes Booth in Ford's Theater in April, 1865.

Although this pretty well exhausts the list of single shot pistols of modern American make, yet brief notice of a .22 target pistol of English make and design may interest American shooting men. This is the one made by Webley & Scott, the well known makers of Birmingham. It is a pistol of the break open pattern, the locking catch being released by pushing forward the inside front of the trigger guard, a clumsy and awkward arrangement, and the catch itself is not very strong or solid, the barrel working loose after a not very great amount of wear. The barrel is accurately bored and rifled, chambered for the .22 long rifle cartridge, and fitted with “Partridge" pattern sights.

One of the best features of the pistol is its large, solid well formed grip, with a solid metal butt piece designed to counteract the weight of the barrel and make the balance of the pistol right, which is a feature also found in the Stevens, Lord, Gould and Conlin Models. The Webley & Scott pistol is not used in this country partly on account of the duty upon foreign arms, but chiefly that in design and accuracy it is in no way superior to those turned out by the American factories.